Jun 15, 2024

War, Money, Oil and the Shaping of Aramco’s Giant Share Sale

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- As the boss of the world’s biggest oil company flew around the world in early June to drum up investor interest in one of the biggest share sales in recent years, he could breathe a sigh of relief.

Five years after Aramco’s $29.4 billion listing had been marred by temper tantrums and U-turns that left it almost entirely reliant on local investors, Amin Nasser and a coterie of top Wall Street bankers had finally delivered the international deal Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman always wanted.

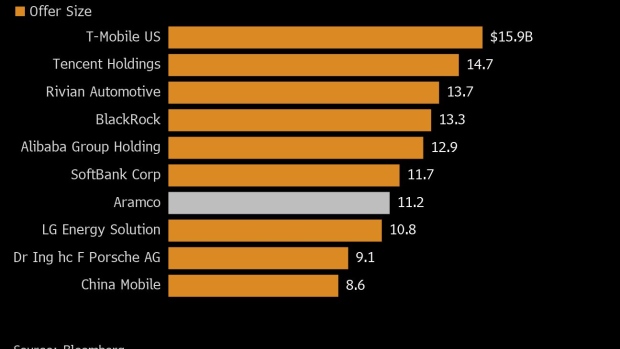

A large chunk of this month’s $11.2 billion share sale was allocated to foreign investors, leading one person involved in the process to describe it as the deal the IPO was supposed to be. Its success could create a template for future Aramco sell downs, which now seem likely as the Crown Prince — who’s known as MBS — seeks cash to help fund his multitrillion-dollar Vision 2030 economic transformation project.

“We’re seeing an ‘all of the above’ attempt to raise investment capital for the Vision 2030 gigaprojects,” said Jim Krane, a fellow at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy in Houston. “Since the hoped-for FDI flows haven’t fully materialized, the Saudi government has turned to its tried-and-true backstop: Aramco.”

This account of the share sale, which Bloomberg News first reported in January, is based on interviews with dozens of people directly involved in the offering, who asked not to be identified discussing private meetings and conversations. Representatives for Aramco and the Saudi government did not respond to requests for comment.

Two Years Out

Back in 2019, Aramco’s initial public offering was marked by bitter clashes between investment banks and Saudi officials, who were angry that the IPO ultimately achieved a valuation of $1.7 trillion, much lower than the $2 trillion they’d hoped for at the time.

This year’s share sale went off much more smoothly. In truth, the offer has been in the works for years and bankers were able to work together more cohesively, allowing the deal to progress in recent months even as war raged across the Middle East, sending the price of oil gyrating in response.

“The increased interest from foreign investors is testament to Saudi Arabia’s success so far in keeping the war in Gaza and its regional repercussions at arms’ length,” said Torbjorn Soltvedt, an associate director of political risk at the consultancy Verisk Maplecroft.

Shortly after the IPO process was finished, Nasser got internal teams preparing for a secondary sale knowing that the kingdom was likely to want to further sell down its Aramco stake. He wanted Aramco ready to sell more shares whenever the government called.

About two years ago, MBS’s closest advisors — including Aramco Chairman Yasir Al Rumayyan — started to hold secret meetings with bankers, investors and consultants to gauge when they could sell off more of the oil giant, which has long been considered one of the kingdom’s crown jewels.

The Finance Ministry had been adding up how much it would cost to deliver MBS’s vision. As it pondered the outlook for oil prices, estimates for government revenue and how much it could borrow while sustaining its credit rating, it foresaw a funding gap ahead.

Foreign direct investment had been picking up, but was still nowhere near where Saudi Arabia needed it to be. Selling off another stake in Aramco offered a good way to help the government bring in more cash.

“The selloff is small enough so that domestic opponents won’t get too upset, and it brings in foreign buyers to test the waters in the kingdom,” Rice University’s Krane said. “If Aramco shares perform as touted, who knows, maybe a few of those buyers will become future foreign investors?”

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine had also caused oil prices to soar to their highest level in years. That’s left Aramco sitting on billions of dollars of cash that it could use to boost dividend payouts. As the largest shareholder, that would help the Saudi state. Boosting the dividend yield would also address one of the major gripes of foreign investors.

Banks ultimately pitched the government committee on a variety of options — including having the sovereign wealth fund, which Al Rumayyan also runs, sell part of its stake in Aramco. Another proposal was a direct sale to other investors. In the end, a committee including Al Rumayyan, Finance Minister Mohammed Al Jadaan, and Economy and Planning Minister Faisal Al Ibrahim, settled on the government paring down its holding.

By the end of last year, the committee had given the deal a greenlight. Now, it was just a question of timing.

Bring Back Bankers

One of the first steps was to bring back the legendary rainmaker Michael Klein as well as bankers at Moelis & Co. as advisers. Both firms had managed to maintain their relationships with the Saudi government after working on Aramco’s IPO. (The failure of that deal to reach the $2 trillion valuation had burned Saudi Arabia’s relations with several other Wall Street institutions.)

They later brought on a series of banks, including Citigroup Inc., Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and HSBC Holdings Plc. Those firms were eventually joined by Bank of America Corp., JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Morgan Stanley.

Unlike during the IPO process, Aramco shares were already trading, meaning there was daily visibility into how investors valued the company. As a result, tensions were markedly lower. Without the backdrop of trying to bridge the expectations of mercurial owners and wary investors, bankers worked better together.

Still, it was difficult to find the right time for the deal: A potential launch in February was planned and then abandoned on concerns about political tensions in the Middle East. A sale in April was considered, but then dropped after Iranian airstrikes against Israel once again heightened tensions.

Markets seemed to be brushing aside each instance of geopolitical tension. Rather than spiking on the threat of widening conflict in the region, the price of oil was rarely above $90 a barrel. Investors, it seemed, were more worried about weak demand than supply disruptions.

The government told Aramco to get the deal done before the second half of June. By then, the fear was that investors had already made most of their allocations for year and that the specter of the US presidential elections would cause turmoil in markets.

Late in the evening on May 30, as bankers across Riyadh unwound amid the increasingly stifling desert heat, phones started ringing. Aramco had formally launched the share sale just a few hours ago. The company already had a large group of banks, but was now spreading the net wider.

Those calls came with a message: You’ve been hired as a bookrunner. Aramco had already secured enough demand to cover the deal but the oil giant wanted to leave no stone unturned. These bankers were told to get ready to join a kickoff call within minutes.

With that, firms including BOC International, BNP Paribas SA, China International Capital Corp. and EFG Hermes were added. SNB Capital was named as lead manager, and a handful of other local banks also made it to the final roster.

$124 Billion Question

Nasser and the banks working on the sale soon took to the road, speaking with more than 100 investors in the lead up to the deal’s official launch on June 2. The road show took them far and wide, talking to regional sovereign wealth funds and the biggest fund managers across the US, Europe and Asia alike.

The deal ultimately priced in the bottom half of a proposed range and about 15% below Aramco’s IPO price, without accounting for bonus shares the firm has issued over the years. Aramco’s market capitalization remains some way off the $2 trillion MBS covets.

Many foreign funds that bought in this time around were passive investors looking to boost their holdings at a discount; there’s also still some concern among some active investors that think the firm remains overvalued and the yield unattractive.

In the end, though, the $11.2 billion that the mega stock offering raised for Riyadh made it the biggest such deal globally in about three years and gave MBS loads of fresh firepower for his plans to transform the Saudi economy.

One key selling point was Aramco’s $124 billion dividend — the world’s largest. The firm’s boosted its payout steadily since listing and the stock now offers a yield of around 6.6%.

Combined with the chance to buy in at a roughly 6% discount, many investors who sat out the IPO decided to jump in this time. About 125 new investors bought shares in this month’s offering.

In all, the deal attracted about $65 billion of orders and almost 60% of the shares went to foreign investors. That’s a far cry from the 23% allocated to foreign investors in the 2019 IPO, giving MBS the international sale he wanted all along.

Overseas demand has been the most interesting aspect of the share sale, said David Rundell, a former US diplomat with decades of experience in the Middle East.

“That is a vote of confidence for MBS,” he said.

--With assistance from Archana Narayanan, Anthony Di Paola and Abeer Abu Omar.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.