Jul 3, 2024

UK’s Motor City Hopes Labour Can Jump-Start EV Battery Dream

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- More than three years have passed since Coventry unveiled plans for a giant electric-car battery factory at its small airport in England’s West Midlands, offering hope that the UK could catch up with rival countries already years ahead in cell production.

But with no major customer or investor, the project has yet to get off the ground, making hollow its target to produce batteries by 2025. Its struggles are emblematic of why the UK’s car industry is foundering.

The upcoming general election could provide a boost. The Labour Party, which is leading in polls, plans to restore a 2030 ban on new petrol and diesel car sales — a move that may finally help the site attract investors put off by mixed messages from the government and the broader EV slowdown.

“That will change the dynamic,” Richard Moore, a former auto executive who’s spearheading the project, said in an interview at the UK Battery Industrialisation Centre next to the airport. The current Conservative government has no clear strategy, leaving potential investors wondering how they would access any state support, Moore said.

The auto industry has been crying out for change since the Conservatives came to power in 2010, presaging a steady decline in car manufacturing. Executives’ biggest complaint is mixed signals from government, noting that Brexit sowed confusion about trade. The decision to push back the ban on new petrol and diesel car sales by five years created more uncertainty about the country’s commitment to EVs.

“They’ve probably done more damage to the UK car industry than any other administration, on both sides, in the past 50 years,” said Andy Palmer, the former chief executive officer of Aston Martin Lagonda Global Holdings Plc and current chairman of EV charging company Pod Point Group Holdings Plc. “The world’s car companies are confused in terms of what to expect from the UK. That’s broken one of the major merits of investments in the UK, which is it’s understandable and predictable.”

Lagging Investment

Once the world’s second-largest car manufacturing hub in the 1950s, the UK has dropped to 18th as of last year, according to the International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers. The country’s efforts to become an early adopter of electric vehicles has stalled, with only one in six new cars registered last year being battery-electric — in line with the year before.

The UK isn’t alone with regard to battery disappointment. Production plans have sputtered across Europe, where countries are struggling to compete with lucrative financial incentives in the US and the stranglehold China has on cell manufacturing.

“The very first question any government coming in has got to ask is: Do we want to stay in the car business?” Palmer said. “Because ultimately, if you want to stay in the car business, you’ve got to make a lot of investment.”

Last year, the Conservative government committed £2 billion ($2.5 billion) to the EV transition, though it also has vowed to reverse an expansion of London’s Ultra-Low Emission Zone that penalizes older, more polluting vehicles.

Labour has pledged £1.5 billion toward new cell factories and committed to a battery-health standard that it says will support the second-hand market for EVs.

Emissions Politics

Both main parties have promised to fix potholes and roll out EV charging infrastructure, but neither has committed to financial incentives to encourage consumers to buy EVs.

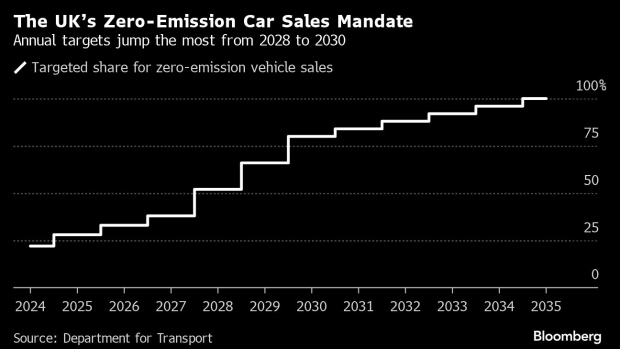

Labour also plans to stick with the zero-emission vehicle mandate introduced by the Conservative government earlier this year. This requires at least 22% of cars sold to be fully electric this year, rising to 80% by 2030. Carmakers face fines of up to £15,000 per vehicle for missing the targets.

Stellantis NV’s UK boss Maria Grazia Davino last week threatened to close van factories in northwest England’s Ellesmere Port and Luton, near London, if the government doesn’t ease targets or introduce consumer incentives. The maker of Peugeot and Vauxhall vehicles employs 2,500 people across the two facilities.

Government investment will be key to enticing the sort of foreign investors that Moore wants in Coventry. The area formerly known as the UK’s Motor City is still home to Jaguar Land Rover Automotive Plc, Britain’s biggest carmaker.

In a blow to the Coventry project, JLR’s owner, India’s Tata Motors Ltd., decided last year to build a £4 billion battery factory in Somerset, with the help of taxpayer support. The government also offered aid to get Nissan Motor Co. to make electric successors to its Qashqai and Juke models in Sunderland.

The UK is still lagging rival countries when it comes to battery manufacturing capacity, with only one operational factory run by Envision’s AESC in Sunderland for Nissan, producing less than 2 gigawatt hours of battery capacity a year. For the automotive industry alone, the UK will require at least 100 GWh a year by the end of the decade, according to a 2022 report from the Faraday Institution. The collapse last year of battery startup Britishvolt Ltd. cast a shadow over the sector.

“No one’s going to take us seriously” until the UK can produce at least 20 GWh a year, said Moore, whose site has planning permission for up to 60 GWh, enough to power 600,000 EVs.

Jim O’Boyle, a Labour councillor for Coventry who used to work at a car factory, blames the government for the lack of progress at the project.

“The frustration has been clear here because they just don’t seem to see it as that important,” O’Boyle said. “I don’t think they’ve understood what the potential benefits are here, never mind what the potential risk is here.”

(Corrects official name of AESC in 17th paragraph.)

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.