Jun 14, 2024

China’s Credit Returns to Expansion as Government Sells Bonds

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- China’s credit growth received a boost from more government bond sales in May, but loans slowed again in a sign of stalling demand.

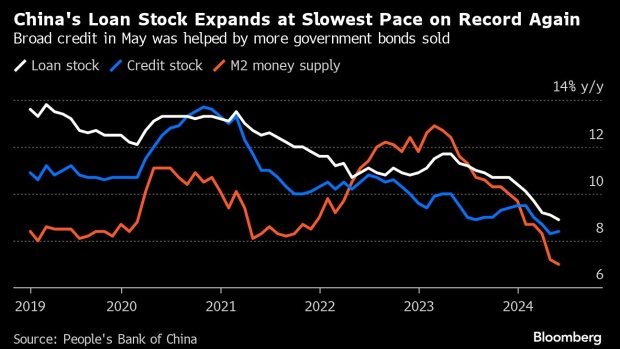

The stock of aggregate financing — a broad measure of credit — expanded 8.4% from a year ago, slightly above April’s figure. The acceleration was largely due to a pickup in government borrowing, with 1.2 trillion yuan ($165 billion) of bonds issued in the month. But the stock of outstanding loans grew at an 8.9% pace, the slowest on record, and the broad M2 measure of money supply growth also weakened.

The numbers show how China’s once-mighty credit engine, which used to power economic growth, is slowing over the longer term. A real-estate slump has damped the appetite for credit among consumers and businesses, while local governments have been forced to pare back their off-balance-sheet borrowing. Beijing is now seeking new ways to sustain economic growth — like high-tech manufacturing — that won’t rely so much on expanding debt.

“Domestic demand is weak and is reflected in poor credit expansion,” said Raymond Yeung, chief economist for Greater China at Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd. “Banks have problems creating loan assets.”

The People’s Bank of China will meet Monday to set a key policy rate, which it’s widely expected to leave unchanged.

Government bonds are accounting for increasing share in the overall credit mix as central and local authorities seek to raise funds for investments that will boost demand and offset the economic damage caused by China’s housing slump. Local governments sold the most debt in seven months in May, while Beijing began issuing the first batches of 1 trillion yuan of special government bonds set for this year.

The rebound in government bond sales and largely stable corporate loans “suggests that infrastructure and manufacturing investments should continue to accelerate,” according to Michelle Lam, Greater China economist at Societe Generale SA.

Weak household borrowing reflects persistent housing market problems and low confidence, she said.

The Chinese yuan was steady after the credit data, set to post a second straight week of declines as the US dollar rebounds.

In one worrying sign for China’s policymakers, the M1 money supply gauge — which includes cash in circulation and corporate demand deposits — fell 4.2% from a year earlier, the sharpest contraction in data going back to 1996.

Economists attribute the drop partly to an exodus from bank deposits that began in April. Investors channeled funds into bonds and wealth management products after policymakers cracked down on companies that took advantage of preferential deposit rates to park cash at banks.

The contraction also points to poor corporate cashflows on the part of property developers who are struggling to sell homes, according to ANZ’s Yeung.

Despite the weak credit growth, the PBOC is likely to hold its fire and maintain its medium-term lending rates unchanged on Monday, according to Zhou Hao, chief economist at Guotai Junan International. Instead, it may choose to provide targeted support to the economy via relending programs, he said.

“As the Fed appears to be reluctant to conduct proactive rate cuts for now, any aggressive policy easing from the PBOC might incur depreciation pressure on the Chinese currency,” he said.

One concern for China’s policymakers is that new credit is often failing to reach the real economy, where it can spur activity and create jobs — and instead just circulating within the financial system.

The cost of some types of short-term interbank loans, known as bankers’ acceptances, fell to the lowest level this year in May, according to data from Zhongtai Securities Co. That’s usually a sign that lenders are swapping these bills with each other to boost loans as they struggle to find companies that want to borrow. Growth in bill financing, which includes such instruments, remained robust in May.

--With assistance from Iris Ouyang and James Mayger.

(Updates with additional details throughout.)

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.