Apr 18, 2024

Venezuela Opposition in Trumoil as Maduro Picks Rival for July Vote

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- A banned candidate is still campaigning. Her replacement is barred from the race as well. And the contender who was allowed to run is seen by many in the fractured opposition as hand-picked by the very president they want to beat.

Turmoil within the coalition opposed to Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro, whose disregard for an agreement for fair elections led the US to reimpose oil sanctions Wednesday, has left the beleaguered nation on the cusp of a July vote that appears virtually certain to keep him in power for another six years.

Much of the infighting is a product of Maduro’s maneuvering. The government barred leading opposition candidate María Corina Machado, then prevented her replacement from registering, allowing Maduro to effectively choose his own challenger: Manuel Rosales, a governor and former presidential hopeful that key opposition figures, including Machado, distrust because of his willingness to negotiate with the current regime.

But the resulting rifts within the opposition are also playing directly into Maduro’s hands.

The Unitary Platform, as the 10-party coalition is known, is now in an uncomfortable position ahead of a Saturday deadline to retire or replace candidates. It needs to decide whether to back Rosales or keep its tentative pick — little-known former ambassador Edmundo González — in the race in hopes that Machado or another candidate may eventually replace him, according to three people familiar with the situation who requested anonymity to discuss internal matters.

A divided vote would essentially erase any remaining hopes the opposition has of dislodging Maduro from the office he has held since 2013.

“Maduro’s strategy has always been the same: discouragement and fragmentation,” said Venezuelan professor and political consultant Carmen Beatriz Fernández. “What we are seeing now with these struggles within the opposition is both things.”

Rosales and González will remain on the ballot if no changes are made. The coalition has little room to maneuver: It can only replace González with Rosales or one of the 11 other barely-known, little-trusted candidates who successfully registered, in hopes that an endorsement from Machado might allow its eventual pick to at least stage an outside challenge.

But Machado, who won a landslide victory in October’s primary, still believes she has a chance to re-enter the race in its final stretch. Government officials have dismissed that as impossible, but she has nevertheless continued to campaign: On Wednesday, she visited San Antonio de Los Altos, a town on the outskirts of Caracas, where a swarm of excited supporters seeking hugs nearly blocked her path to a stage.

‘Don’t Drop Out’

Maduro, meanwhile, has urged Rosales to remain in the race, and even allowed Colombian counterpart Gustavo Petro, a key regional ally, to hold a meeting with him in Caracas last week, in an attempt to paint the governor as the most relevant opposition figure.

“Don’t drop out, Manuel, I’ll wait for you on July 28,” Maduro said during an appearance on state TV this week.

The Venezuelan leader needs at least one credible contender to legitimize the vote’s results in front of electoral monitors.

The European Union’s parliament, however, said in February that it will not recognize any vote that doesn’t include Machado, and in reinstating the oil sanctions, the Biden administration said Maduro had failed to comply with the elections agreement that led to limited relief. Nearly every major Latin American leader — including Brazil’s Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, a traditional ally — has criticized Maduro for banning candidates.

The regime has also continued its crackdown on the opposition, ordering the arrests of roughly a dozen of Machado’s allies and aides. Six opposition figures remain hidden in the Argentine embassy in Caracas nearly two weeks after Venezuela said it would grant them safe passage out of the country.

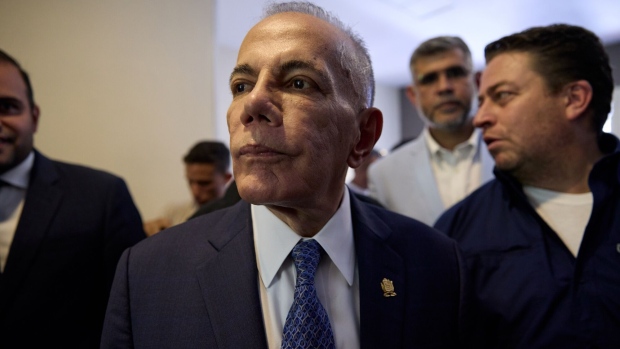

Rosales would have to make up considerable ground in polls to pose as big a threat to Maduro as Machado potentially could. The 71-year-old is an experienced politician in his second stint as governor of Zulia, a key oil-producing state near the Colombian border, but has had little success on the national stage.

In 2006, Rosales lost to then-President Hugo Chavez by 26 points, and his popularity among Venezuelans is currently below 20%, according to an April poll from Caracas-based firm More Consulting. That puts him six points behind Maduro and more than 30 short of Machado, whose 51% approval made her the most popular politician in the survey.

Despite the increasing odds that he will sail to victory in a race foreign governments are unlikely to recognize, Maduro has continued to shrug off blame for the opposition’s woes.

“Is it my fault?” he asked earlier this week during another TV appearance. “Am I really that smart that I have been able to divide the opposition like this?”

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.