Jun 27, 2024

Macquarie Borrowed Big. Now 16 Million Thames Water Users are Picking Up the Bill

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Steady revenue. Little controversy. And institutional investors tripping over themselves to be involved. Water was supposed to be a boring business. Yet Macquarie Group’s decade as owner of Thames Water was anything but.

Funds managed by the Australian bank and asset manager made about £930 million ($1.2 billion) by selling off a 48% stake in the UK’s biggest water company before 2018, according to a person familiar with the deals and Bloomberg calculations. Those who bought that stake from Macquarie now regard it as virtually worthless, with one shareholder writing off almost £1 billion it invested.

On top of the profit Macquarie made on the sale of its equity in the firm, the utility also paid out about £1.1 billion through dividends and interest payments on shareholder loans, filings show, of which funds managed by Macquarie received £508 million corresponding to their 48% equity stake. Macquarie’s investors made a return of around 2.5 times on their original investment in Thames Water over its 11 years in charge, according to the person — roughly £1.65 billion. No dividends have been paid to the utility's ultimate shareholders since Macquarie exited the business in 2017.

The previously unreported figures show the extent to which Macquarie was able to take advantage of industry rules and leverage to supercharge a water company generating stable revenues, into one capable of producing cash to pay investors high dividends.

Interviews with several people familiar with the company and its regulator, Ofwat, during the period of Macquarie’s ownership paint a picture of an adroit financial operator. One that was helped by a flawed Ofwat-managed pricing system which encouraged water companies to take on ever greater levels of debt. That indebtedness has left parts of the industry struggling to survive.

None is more exposed than Thames, which is often seen as the embodiment of the failings in the UK water industry. Its future has become an issue in the July 4 general election with a new government facing the possibility of having to bring the water utility into special administration or temporary state control. It comes against a backdrop of untreated sewage pumped into rivers and seas, the prospect of a 56% increase in bills up to 2030, and creaking infrastructure that have sparked anger among the company’s 16 million customers and politicians.

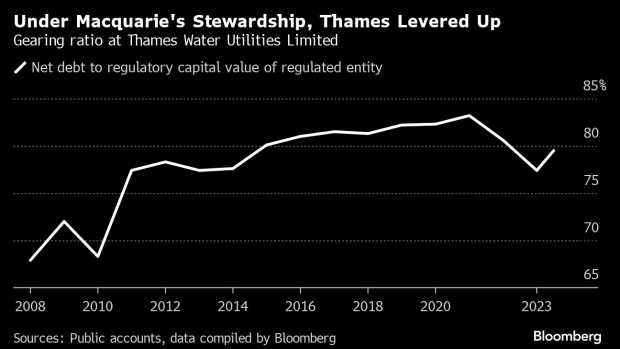

The precarious finances at Thames pose an existential threat. Before Macquarie bought the utility in 2006 it had net debt of £2.4 billion at operating company level. By the time the Australian group sold up a decade later that had more than quadrupled to £11 billion. Debt in the operating company — the part regulated by Ofwat — now stands at £14.7 billion.

Macquarie has said that debt raised at Thames helped fund necessary investments into the network. And while it acknowledged that debt as a proportion of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization did increase under its ownership, it said this was down to regulatory changes.

Yet that debt — at a time of higher interest rates — has crippled Thames and its parent company Thames Water Kemble Finance Plc, which Macquarie helped create before the 2006 purchase. In April Kemble told investors it would default on its debts, and its bonds due in 2026 are now virtually worthless.

Ofwat will make a draft ruling on whether Thames's next five-year business plan is viable on July 11. Without the nod from the regulator Thames may find it impossible to raise the billions of pounds in equity needed to fund its turnaround plan to fix chronic leaks and the sewage spills. On Monday the UK’s main opposition Labour Party — which looks poised to take power after the election — said it wanted to avoid any kind of long-term state ownership of Thames and is searching for alternative solutions.

The Ofwat review — which will set consumer prices and determine how much it will cost water companies to borrow — will be the most consequential since privatization in 1989 because the political stakes are so high. For Ofwat, making the right assumption is critical. It needs to show that it's protecting consumers and keeping bills down, while also helping to drive long-term investment in the industry. The final Ofwat decision is expected in December.

Thames has requested more favorable terms from the regulator in the hope of attracting investors. Chris Weston, the utility’s chief executive since January, has said that once Ofwat makes its decision he will go to the market again to find new investors.

That hunt for new backers was made more difficult when one of the two investors who bought stakes in Thames from Macquarie in 2017 — the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System — wrote off the entire value of its £990 million stake in Kemble. Other investors are expected to lose equally heavily.

If Ofwat sets a low Weighted Average Cost of Capital or WACC — the regulator’s best guess of how much it will cost water companies to borrow money and invest in infrastructure over a five year period — it could be all but impossible for Thames to avoid insolvency. Weston has said that the company, which has enough money to operate until July 2025, has other options to explore before reaching that point.

“If the current owner is valuing at zero a company that's not just a natural monopoly, but a statute monopoly and an essential service with a growing population, with no competitors, I would think it would take quite a lot to persuade any other investors to start buying this company,” said David Hall, visiting professor at London’s University of Greenwich who has written extensively on the water industry. “The alternative private sector owner option is now disappearing fast for all the companies, but I think must have disappeared completely for Thames Water.”

Financial or Structural Engineering?

The seeds of the crisis were sown 15 years ago in the depths of the financial crash, say company and industry insiders. Macquarie, and other water company owners, were encouraged to raise debt after Ofwat set an implied cost of borrowing — part of the WACC — at a level far higher than was needed for the firms to raise financing. It meant that every time a bond was issued Thames or other water companies made money from the difference between the theory and the reality.

In the first full year after the Macquarie-led 2006 takeover, the regulator allowed for an implied cost of borrowing of 4.3% while Thames Water issued a series of inflation-linked bonds totaling £1.1 billion, all with an interest rate of less than 2%. This financial arbitrage incentivized many water companies to raise debt.

Part mathematical formula, part academic exercise, the WACC can only ever be an educated guess. But it has taken on totemic importance in an industry strapped for cash. In effect, the companies, all monopolies, are given permission by the regulator to make a certain level of return, but the process is more akin to a thought experiment than a functioning market price. Only since 2019 has Ofwat, which said it could not comment during the election campaign, indexed the cost of debt to a market benchmark which protects against changes in the cost of finance.

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, Ofwat officials were in a bind. They needed to set the WACC for 2010 to 2015 without any idea of which way interest rates were heading. So they set it at 3.6%.

They couldn't have been more wrong as borrowing costs were forced ever lower by central bankers dealing with the fallout from the crash.

Officials acknowledge that they relied too heavily on credit ratings companies to prevent the utilities from taking on too much debt. Many water companies retained healthy ratings even as they became more and more indebted.

“When the great financial crisis happened and interest rates went to the floor, Ofwat never revised what the cost of capital was,” said Tim Whittaker, a research director at the EDHEC Infrastructure Institute. “For years, Macquarie got away with just gearing up the balance sheet adding as much debt as it could, and it allowed them to rip that cash out essentially without the investment in the business itself.”

With Thames issuing cheap debt, money generated by the business could be returned to shareholders. Between 2010 and 2014, more than 70% of the cash available at Thames was sent to investors in the form of dividends and loan repayments, according to EDHEC analysis. Shareholders received nothing in 2007, and then more than £100 million in 2008. The payouts continued until 2017, totaling more than £1 billion in all, a large chunk of which would have gone to Macquarie.

A spokesperson for Macquarie said it could not comment on the EDHEC calculations. But said that: “In our period of ownership we helped Thames Water invest more than ever before, or since, as well as achieving improvements in important measures of operational performance: reduced leakage, fewer pollution incidents and improved drinking water quality.”

“Much more needed to be done to further improve Thames Water’s performance,” added the spokesperson. “However, when we sold our stake in the company it was meeting the conditions set by the regulator, had an investment grade credit rating, and had generated returns to our investors in line with its listed UK utility company peers.”

After 2014 Ofwat made it harder for water companies to raise debt and investor returns were dramatically cut. But it took almost a decade for Ofwat to gain powers to stop water companies from paying dividends to service the debt of their parent companies as Thames had done with Kemble.

Officials speaking on condition of anonymity said that until 2021 they had to rely on coercion and embarrassment to achieve reductions in leverage. But in April 2023, Ofwat announced that poorly performing companies wouldn't be allowed to pay dividends. Just seven months later, Thames paid Kemble £37.5 million to service its debt and Ofwat started the investigation that ultimately led to its shareholders cutting the company off from new equity.

Hall characterizes the current situation as a “belated political economy standoff” between the regulator and the companies over the question of whether shareholders are prepared to put in their own “capital to finance necessary investments for our public services.’”

Of the £11 billion Macquarie invested in Thames Water infrastructure during its ownership, more than 85% was funded by debt. The remaining 10% to 15% was equity generated by the business, also known as retained earnings.

By the time Macquarie sold its final stake in 2017, the bank says the regulated capital value of Thames Water had grown to £12.9 billion through investments to improve the network. It argues that it ran Thames with a prudent level of leverage, and that the annual returns of 12%-13% were only a little higher than Ofwat’s baseline level of roughly 10%.

“It’s disappointing that the UK media has chosen to have a very narrow narrative on this and make a big deal of the debt in Thames Water, trying to link it to us who didn’t own the asset for six years now.” Macquarie Chief Executive Officer Shemara Wikramanayake told the group’s annual general meeting in 2023.

“It was investment-grade when we stopped owning the asset,” Wikramanayake added, referring to Thames Water’s credit rating.

The Macquarie Affair

Macquarie’s affair with the British water industry began two decades ago when it spotted opportunities in the fragmented monopolies washed up by the 1980s privatization of the sector.

It bought South East Water Ltd. for £386 million in 2003, before selling it three years later for £665 million and bidding for Thames, then owned by German energy company RWE AG. The Australian bank led a consortium that bought the firm for £4.6 billion in 2006, taking a 48% stake and responsibility for managing the company.

The new owner was hands on, according to people who worked there at the time and determined to cut costs and simplify the business. With prices set by the regulator, keeping costs low, along with leverage, was the best way to drive shareholder returns.

The gearing — a measure of debt relative to capital at a utility — ultimately reached more than 80% at Thames Water as Macquarie sold down its stake in the company in three tranches between 2011 and 2017. With low interest rates the debt load looked high, but manageable. Then one day it wasn’t. Almost two-thirds of the company’s debt was linked to inflation or carrying floating rates, keeping issuance costs low. That backfired when prices soared in 2023.

The debt that Macquarie loaded on to Thames has proved unsustainable. Kate Bayliss, an economics research associate at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies, likens Thames customers to renters of “their water system” who are having to pay “their landlord’s mortgage while the repairs are not being done.”

The landlord is now in arrears and the fight is on over whether the tenant’s rent needs to go up, or the lenders need to take some losses. The original landlord, Macquarie, is long gone. Instead it will be for a new UK government to determine what happens next.

(Updated to add extra comment)

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.