Jul 3, 2024

Carbon Offsets Endorsed by Key Oversight Body Questioned by NGO

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Some carbon offsets that received a stamp of approval from a key industry body could be environmentally worthless, according to a new study from a watchdog group. The finding raises questions about the efficacy of a long-awaited system meant to improve the quality of credits and help companies avoid greenwashing.

Companies buy carbon offsets as a way of funding sustainability initiatives to try and make up for their own pollution. Demand slumped in the $1 billion market after a string of controversies and lawsuits made businesses wary of backlash for supporting projects that don’t deliver on their promised climate impacts. Some investors remain optimistic that standards-setting bodies can restore confidence and spur growth.

The Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market, an industry-led governance group, has been trying to solve the problem with guidelines, called the Core Carbon Principles (CCP). These have been endorsed by the International Organization of Securities Commissions, the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission and the Biden administration. (Mark Carney, chair of Bloomberg Inc., is part of ICVCM’s distinguished advisory group.)

To carry the CCP label, a credit must be issued by one of the five offsets programs that ICVCM has vetted and generated using an approved methodology, but the group does not make project-level evaluations. Last month, ICVCM announced the first two categories to be green-lit: projects that capture and destroy methane from landfills and those that remove ozone-depleting gases from discarded equipment such as air conditioners.

CarbonPlan, a research nonprofit that specializes in offsets and has spent years examining dozens of projects, studied some of the landfill credits that are now eligible to carry the CCP label. That analysis found some of the credits didn’t succeed at “additionality,” a measure of whether the extra funds they generated resulted in a change that wouldn’t have happened otherwise. CarbonPlan argues that six of the 14 projects likely failed this test.

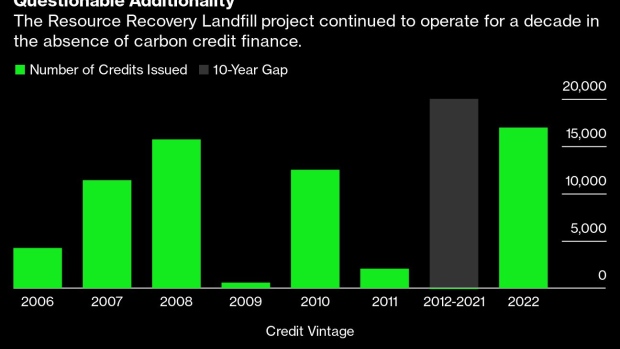

An example is the Resource Recovery Landfill project, which captures methane emitted from a municipal waste dump in Cherryvale, Kansas, and burns it to produce water and carbon dioxide, a less potent greenhouse gas. The project issued carbon credits from inception in 2006 to 2011. It then stopped, which is commonplace: once a project is financially viable, either through the market or government support, it’s no longer eligible to generate offsets.

CarbonPlan’s analysis, based on US EPA data, showed Resource Recovery was able to keep capturing methane even when it wasn’t selling credits and in fact grew its number of gas extraction wells during those years. That’s why it was surprising that the project started issuing credits again in 2022.

“Given that the landfill's gas collection system operated for 10 years without carbon financing, it does not seem credible to claim that the methane [produced in 2022] would have otherwise vented to the atmosphere,” said Grayson Badgley, a research scientist at CarbonPlan.

Amy Merrill, chief executive officer at ICVCM, said the group seeks to supervise the CCP-labelled market to ensure its rules are being adhered to, including on additionality. She said ICVCM will investigate and engage with carbon credit programs where issues like mislabeling are identified.

Part of what makes these evaluations inherently difficult is that those taking stock are removed from the underlying projects and the projects themselves began long before the new standards. Resource Recovery is monitored by Climate Action Reserve, which brought the landfill offsets methodology for approval by ICVCM. Craig Ebert, president of Climate Action Reserve (CAR), said he saw no problem with a long pause in the landfill generating offsets. In some cases, he said, it might cost a developer more to generate offsets than what it would earn from selling them.

CAR’s assumption is that the developer would have included the estimated revenue they’d make from offsets in their original business model, meaning those projects wouldn’t have gotten off the ground if they didn’t think they could rely on funds from carbon credits in the future, Ebert said.

But CarbonPlan's review found Resource Recovery's landfill offsets was among several other projects that it deemed "non-additional" because they were designed as far back as 2006, making it unlikely they budgeted for a change that came in 2019 allowing for offsets revenue continuing past the first decade of operation. “It’s hard for me to imagine that these landfills built the possibility of a future protocol change into their revenue models,” Badgley said.

CAR uses a standardized approach to judge additionality and doesn’t inspect individual projects because those assessments are subjective, Ebert said. A spokesperson for Republic Services, the $60-billion company that runs Resource Recovery, said the project was verified by a third party using an approved methodology.

This confusion over carbon offsets from landfills in the US might seem like a niche issue but the standards developed by ICVCM are going to become widespread. Only about 27 million credits are now eligible to carry a CPP label, making up a 1.6% sliver of the total offsets market. But ICVCM is in the process of assessing a further 27 categories of credits, covering around 50% of the market, including the popular but controversial REDD+ forest-protection approach. Soon many offsets on the market could carry this seal of approval.

ICVCM has already drawn criticism for its high-level approach, which skeptics have said isn’t enough to weed out low-quality offsets. CarbonPlan says its analysis shows those limits in practice.

“The ‘CCP-approved’ label is not an unambiguous signal of credit quality,” the group wrote in its report. “We urge market participants to adjust their expectations about what the ICVCM assessment process can deliver.”

Listen on Zero: How Did a Good Idea — Carbon Offsets — Go So Wrong?

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.