Feb 2, 2023

Why We Shouldn’t Confuse Peak Oil With the Price of Bananas

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Four years ago Guy Debelle, then the deputy governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia, delivered a speech on climate change and the economy. In it he said that the central bank’s response to supply shocks historically has been “to look through the impact on prices, on the presumption that the impact is temporary.” As an example, he cited banana prices following a 2011 typhoon: The price spike was enough to boost inflation 0.7%, but once the crop returned to normal, inflation settled — and bananas were therefore not a central banker’s concern.

The speech is worth recalling not because of the bananas but because of the questions Debelle raised next. What if climate change is something that central banks cannot just “look through”? What if its impacts are not “temporary and discrete,” as after that 2011 cyclone, but more permanent?

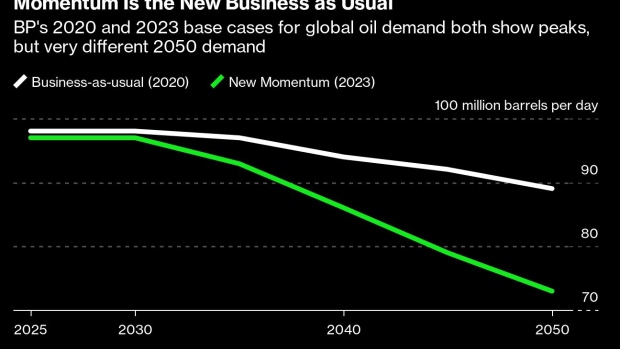

I think of the speech today after reading BP Plc’s latest energy outlook. According to BP, global oil demand has already peaked. Even under its most conservative scenario (“New Momentum”), it puts peak oil behind us and sees demand falling by about a quarter to mid-century. More aggressive scenarios have demand falling much further, by almost 80%, in a net zero future.

But this is not the first time BP has made the peak-oil call. It first did so in 2020. Then, it predicted much less of a future decline than the 2023 outlook does. In 2020, Covid-19 was not expected to shift oil demand permanently down in a base-case scenario. It was, as Debelle might say, temporary and discrete.

Today we are in another shock — the energy shock following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — but it is different from 2020, too. We’ve had three more years of the push to develop and deploy electric vehicles, and future impacts on oil demand look clearer. It is increasingly possible to substitute oil in road transport; more than that, it is increasingly expected that this substitution will happen on a global scale. But it is not just oil where war’s impacts look close to permanent.

In its structural responses to the war, Europe is redrawing energy maps in ways that may prove lasting. Gas networks from points east are a chokepoint now, not a supply line. Some have been blown up and will probably never supply a molecule of methane. The US is now (tied as) the world’s biggest supplier of liquefied natural gas, and Europe, not Asia, is the biggest buyer.

Wind and solar together are a larger source of electricity than either coal or gas in the European Union, even with a rebound in coal consumption last year due to throttled gas supply. Total fossil-fuel power generation in the EU could drop another 20% this year, according to the think tank Ember.

A wave of policies in Europe and the US are also transforming energy trade. Some of it is climate policy, such as the EU’s Fit for 55 law targeting a 55% emissions reduction by 2030. Some of it is industrial policy, such as the many domestic manufacturing provisions of the US Inflation Reduction Act.

And everywhere there is an impetus to reduce exposure to imported energy. That is not to say that it is entirely possible to reduce that exposure (in particular with OPEC likely to contribute a larger share of oil supply over time). The only way to get exposure to zero is to forego imports completely.

In 2020, BP still referred to its base case as “Business-as-usual.” Three years later, the base case is “New Momentum.” This change does not look temporary or discrete, in central banker’s language. Instead it looks like something permanent. And it is not just oil demand that looks to be peaking in a permanent way; it is demand for all fossil fuels.

Commenting on the BP report online, Kingsmill Bond, an energy strategist at the research nonprofit RMI, said the oil major “calls time on the fossil fuel era.” This follows the same call coming from think tanks, “then the IEA, now an oil company,” he added. “Consensus is shifting, and fast.” A fossil fuel peak is here. Technological momentum towards decarbonization is the new business as usual.

Nat Bullard is a senior contributor to BloombergNEF and Bloomberg Green. He is a venture partner at Voyager, an early-stage climate technology investor.

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.