Mar 2, 2021

Trudeau's debt binge shows limits in Canada's sharp contraction

, Bloomberg News

Bureaucracy masking state of Canadian municipal budget finances, says C.D. Howe CEO

Justin Trudeau was more committed to borrowing his way out of the COVID-19 crisis last year than almost any other leader in the developed world. That cushioned the blow of the pandemic, but raises some hard questions about what Canada got for all that spending.

The economy shrank 5.4 per cent last year, Statistics Canada said Tuesday, the sharpest annual decline in the post-World War II era and the third straight year in which it underperformed the U.S. economy. That’s despite Canadians receiving $20 (US$16.55) in government transfers for every dollar of income lost, according to government data.F

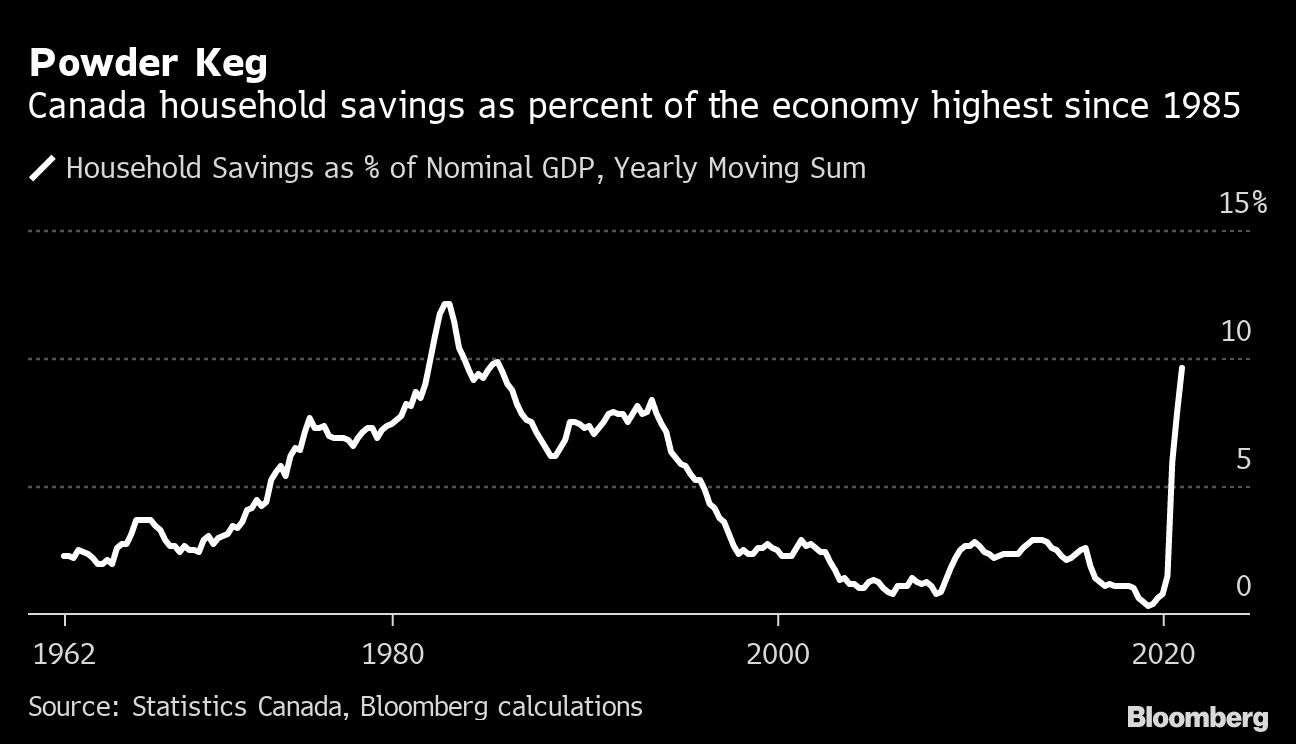

Treated to larger handouts, Canadians mostly hoarded them, potentially opening Trudeau’s government to criticism it has wasted money on programs that spread cash quickly but inefficiently. As one opposition lawmaker likes to put it: “The government spent the most to achieve the least.”

The rise in savings is a phenomenon in other countries, too, including the U.S., where Americans have added US$1.7 trillion in extra savings, according to data from Bloomberg Economics.

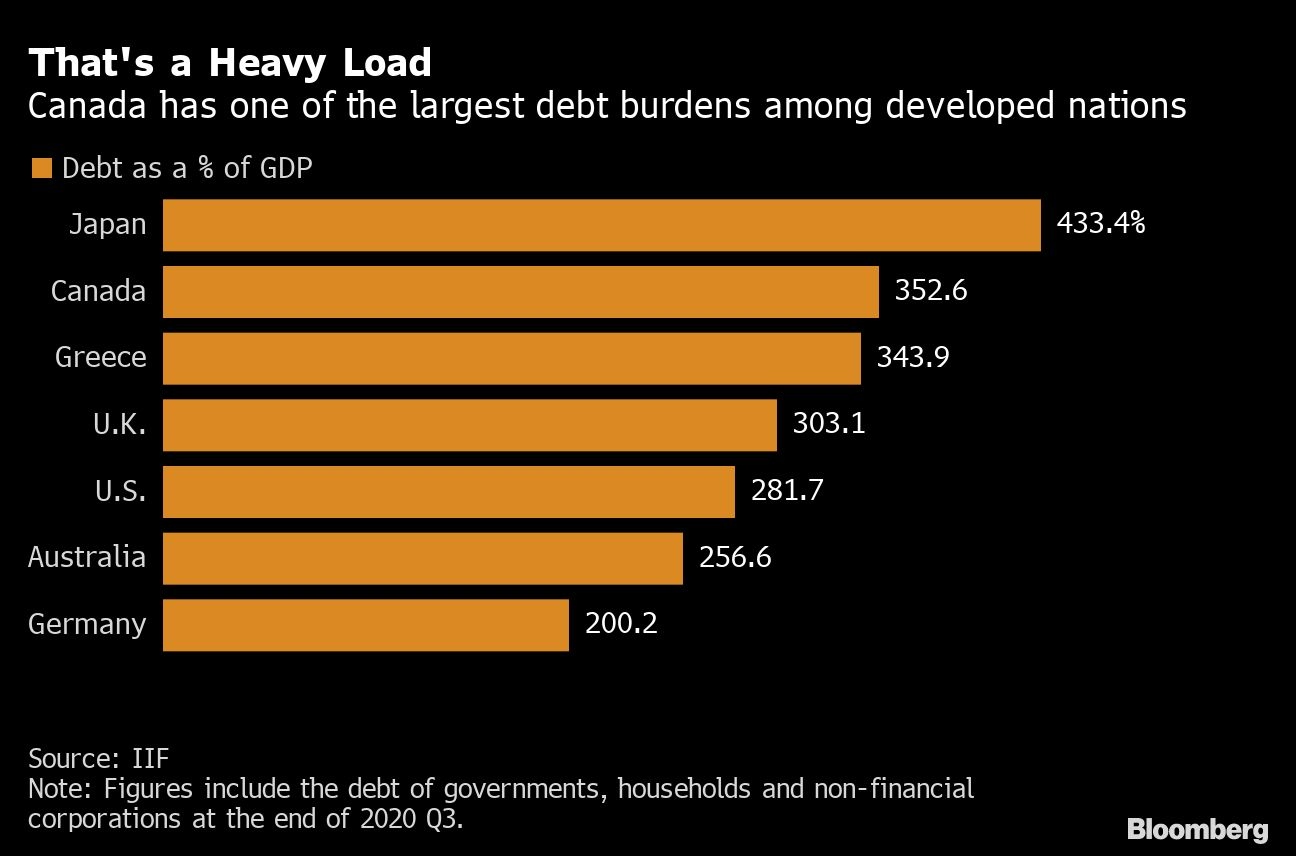

In Canada, the concern is more acute, though, because the money the government borrowed to finance stimulus programs contributed to one of the biggest increases in debt among advanced economies last year. Total public and private debt rose about 50 percentage points to 353 per cent of gross domestic product as of the end of the third quarter, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Government officials and many economists brush off the criticism, claiming it misses the point. For one, it suggests that policy makers had the luxury of precision last March and April as they were rushing to prevent a depression.

Stephen Poloz, governor of the Bank of Canada when the crisis hit, quipped at the time: “No firefighter ever got criticized for using too much water.”

The government’s key early move wasn’t a one-time US$2,000 check but a $2,000 monthly payment to those who’d lost jobs or income because of the virus. Trudeau also offered money to students with poor summer job prospects, and to pensioners, indigenous people, artists and others.

Fiscal Capacity

Economists give the prime minister high marks for acting quickly, but the end result has been an overshoot. Government transfers to households increased by $119 billion in 2020 from a year earlier, versus a decline of just $6 billion in regular income.

There’s still the prospect that some of the excess savings will flow back into the economy sooner than anticipated, fueling an even strong recovery in 2021.

Fourth-quarter growth was stronger than anticipated, adding to optimism about a rebound fueled in part by climbing prices for oil, the country’s top export, though official data revealed some underlying problems as well. Both business investment and household consumption remain soft.

“Obviously knowing now this was going to happen, they wouldn’t have been as generous. But it was a game-time decision,” Jean-Francois Perrault, chief economist at Bank of Nova Scotia, said by phone. “Was that the right thing to do, I guess the answer -- or part of it -- will be revealed in the next few months.”

Trudeau has defended the size of the deficits by saying they relieved pressure on families carrying some of the highest household debt levels in the world. If his government hadn’t responded with swift measures, “what would Canadians have done? They would have loaded up their credit cards,” the prime minister said last summer. Instead, personal insolvencies are the lowest in almost two decades.

But the bill will show up in other ways, according to economist William Robson, chief executive officer of the C.D. Howe Institute in Toronto.

“The federal government’s capacity to deliver future services has deteriorated spectacularly,” he said in an interview. That includes the ability to address any future economic setbacks or finance longer-term challenges like aging infrastructure and climate change. Tax increases are a near-certainty, Robson said.

Spending Expectations

Trudeau’s governing Liberals are already showing relatively more restraint in setting expectations for spending.

Even as emergency programs have been extended, there appears to be little appetite for an additional stimulus package that comes anywhere near the Biden administration’s US$1.9 trillion plan in the U.S.

Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland has plans for more spending but has pledged to keep any additional top-ups at a modest 1 per cent to 2 per cent of GDP.

The jump in the savings rate, which was a still-elevated 12.7 per cent in the fourth quarter, clearly preoccupies Freeland, who has argued it will eventually be spent once confidence improves. To emphasize the point, she’s rebranded the government’s efforts last year as a “preloaded stimulus.”

That theory has its doubters, starting with the Bank of Canada, which has previously said it isn’t counting on the built-up savings to be unleashed quickly. Canadians may instead hang onto the money or use it to pay down their own sizable debts, the bank says. That wouldn’t be a trivial outcome, either.

Frances Donald, global chief economist and head of macro strategy at Manulife Investment Management, said it’s misleading to use short-term economic data to measure the effectiveness of fiscal stimulus.

To Donald, what matters is the damage the spending prevented -- it reduced long-term scarring in the labor market and prevented bankruptcies and poverty, helping the country get to the other side of the pandemic in better shape.

“The value of fiscal support will show itself when the vaccine arrives and the economy reopens,” she said.

Vaccine Woes

Yet Trudeau remains vulnerable. There have been concerns from insiders in the finance department that his government has used little economic analysis to direct pandemic spending.

He could wind down emergency programs faster if Canada had enough vaccines, but that campaign has been slow. The country has administered just 5 doses per 100 people, and only 1.4 per cent of the population is fully vaccinated, according to the Bloomberg Vaccine Tracker.

Vaccines are Trudeau’s biggest political problem right now, and it’s the major reason why his approval rating dropped to 45 per cent in a recent Angus Reid Institute poll, near the lowest since the pandemic began. He has promised the vaccine pace will accelerate and that all eligible Canadians who want a shot will get one by September.

“I wouldn’t go so far as to say there’s too much stimulus given we have an unemployment rate above 9 per cent,” Doug Porter, chief economist at Bank of Montreal, said in a telephone interview. “What I would say is that expectations of another big wave of stimulus might suggest at some point we could be looking at too much.”

--With assistance from Erik Hertzberg and Derek Decloet.