Dec 3, 2020

The secret to Order of Canada inductee Denham Jolly's multi-million dollar empire

By Anne Gaviola

What you need to know about new Order of Canada inductee Denham Jolly

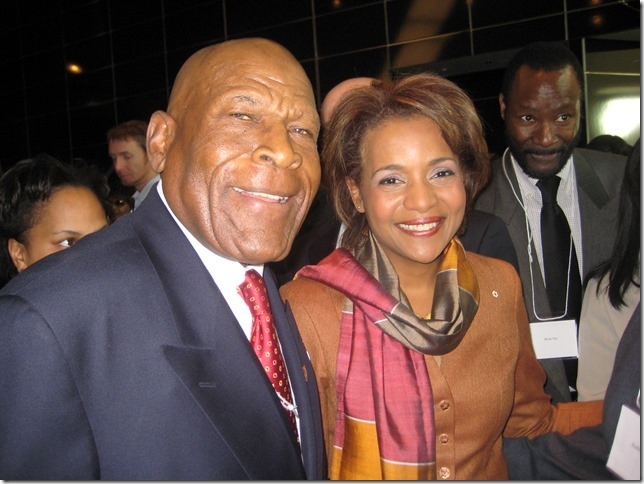

Denham Jolly is a man of many titles: Businessman, human rights activist, author and philanthropist. And in a phone interview from his home in Toronto, the 85-year-old describes himself as “a serial entrepreneur.”

Jolly’s empire, which he began building at age 33, started with the purchase of student rental housing in downtown Toronto, made possible with a loan for the $5,000 down payment. Building on that success, he went on to purchase retirement and nursing homes in Canada and the U.S., a Days Inn motel, medical laboratories as well as a Toronto-based publishing company.

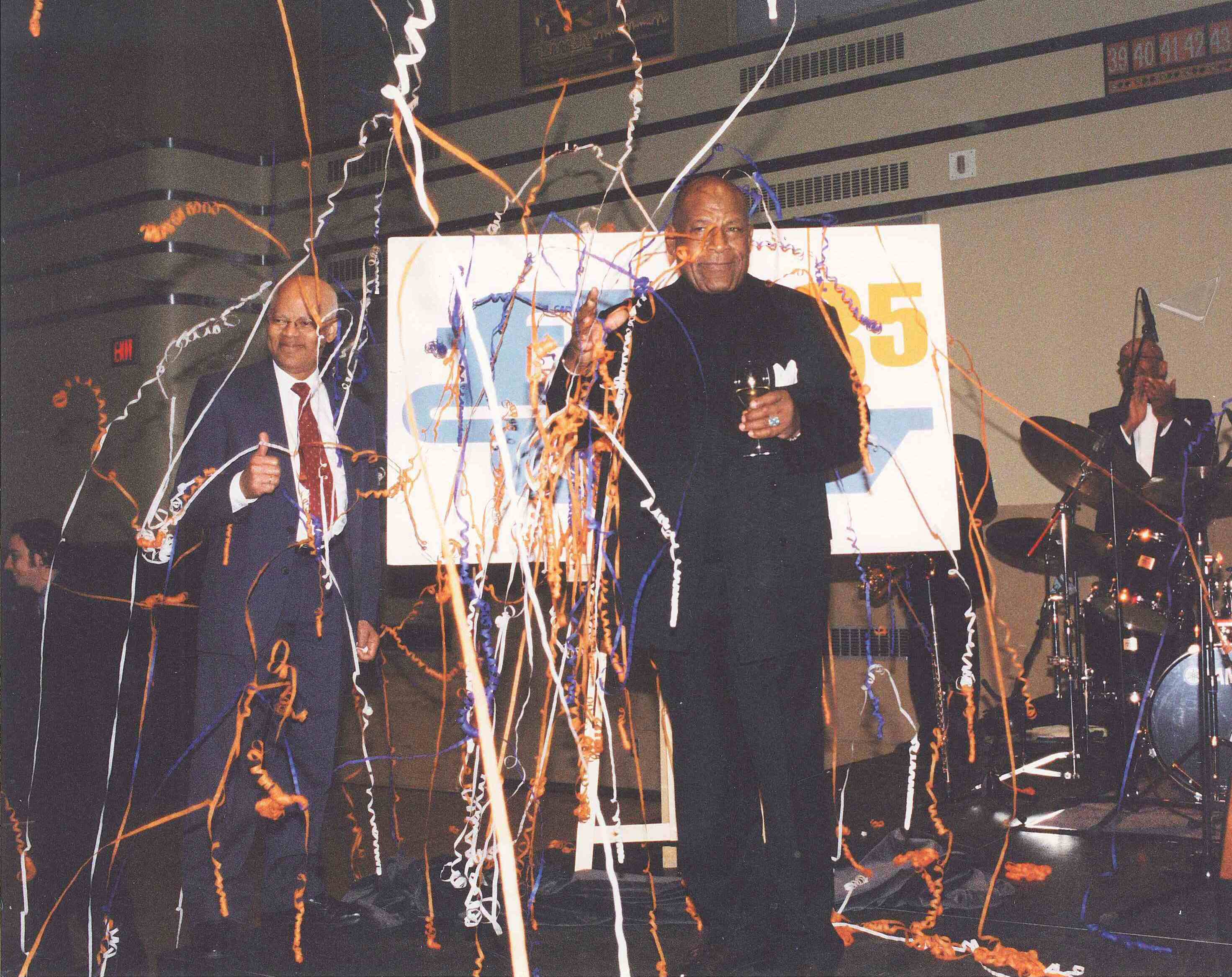

But he is perhaps best-known for his tenacity in launching Canada’s first Black-owned radio station, FLOW 93.5.

That lifetime of work for social justice and the breadth of his financial success was recognized Friday when Jolly was appointed a Member of the Order of Canada, one of the country’s highest civilian honours. He joins 114 other appointees including Whitecap Dakota First Nation Chief Darcy Bear as well as Olympians Tessa Virtue and Scott Moir.

When pressed about his net worth, Jolly says it’s “somewhere between $20 and $30 million dollars.” And when asked to share something surprising about himself, he says: “I know some people think I’m hard-nosed but I have a heart.”

Though the founder of the Black Business and Professional Association is proud of his entrepreneurial acumen, Jolly says he is most proud of his three children and his philanthropic efforts. When asked what keeps him up at night, he cites injustice and inequality that he views as “rampant” in our society.

Early days in Canada

Jolly was born in Green Island, Jamaica and first came to Canada at age 19 to attend McGill University in Montreal where he graduated with a Bachelor of Science. Back then, newcomers such as himself on a student visa had to check in every three months with Immigration Canada “like a parolee.” In 1960, Canada was freely accepting immigrants from Europe, but, in Jolly’s view “did not want Black people in Canada.”

Despite obtaining his science degree in three years and graduating in the top fifth percentile of his class, he was told to “go home” after completing school. “I had no choice,” he says. “It was either that or jail, where they put refugees.”

He returned to Jamaica but came back to Canada for “more opportunities” and a better life in 1962. He says a “drinking buddy” with ties to the Canadian consul helped him get his papers.

Jolly worked briefly as an air pollution monitor for the City of Toronto, which involved scaling icy heights during the colder months before taking high school teaching jobs in Sault Ste. Marie followed by Forest Hill Collegiate in one of Toronto’s most prestigious neighbourhoods.

Meanwhile, Jolly’s side hustle in the late 1960s, renting to students after the purchase of a rooming house on the University of Toronto campus, was becoming more profitable. He eventually left teaching to expand his business.

Canada's first Black-owned radio station

It was after his purchase in 1982 of the weekly publication Contrast – Canada’s first newspaper for the Black and Caribbean diaspora – that Jolly recognized the need for daily news that served his community.

“We needed a radio station,” he says. “Plus there were a lot of promising Black artists but no Black music being played on any radio stations in Toronto — it was forbidden on some stations. You had to tune in to Buffalo or Detroit to listen to Black music.”

Jolly saw an opportunity and applied for a radio station licence. It would take him three tries, 12 years and nearly $1.5 million dollars to accomplish this. Local media and The Washington Post chronicled his plight as a battle against racial barriers in Canada.

“I decided, I’m not going to let you guys dissuade me or beat me down. I’m going to stay in your face,” Jolly says. “It was a lot of money back then, not to mention the time spent. We had to hire lawyers, engineers, consultants, rent an office. Eventually, we got it.”

That station is FLOW 93.5, which in 2001 became the first mainstream station to play hip-hop in Canada and went on to be the first to play Drake. With Jolly at the helm, the station hired Black employees ranging from accounting to its broadcasters, launching many careers.

Racism in Canada

According to Jolly, the notion that racism exists because the system is broken is a fallacy.

“It’s not broken, it was built that way on purpose to preserve the status quo,” he says.

Jolly says he has been on the receiving end of subtle and not-so-subtle racism over the years. He wrote about his experience with “polite” racism in Canada in his 2017 book In The Black: My Life.

For BNN Bloomberg, he recalls a conversation with a bank manager in the 1980s.

“I had a bank manager tell me ‘I’ll lend you money but I wouldn’t want you marrying my daughter.’ He says that to my face,” Jolly says.

He says he was treated differently than his peers because of his race, which is why he would send his white accountant to deal with banks whenever possible. When he looked at potential houses to live in, he would bring a white friend and pose as her contractor. Jolly says this was necessary to avoid discrimination.

In the late 80s, Jolly says he had a $3-million loan on a nursing home coming due and there was no problem, until he deviated from his cautious strategy.

“I made the mistake of going to a function where the bank manager was and he discovered I was Black,” he recalls. “Up until then, everything was fine with the loan but the next day he says they couldn’t go ahead with it.”

When asked if things have gotten better over the years, his answer is quick and without animosity: “No, not much.”

Secret to his success

According to Jolly, the key to his success involved being several steps ahead of everyone — his competition, his creditors, his bankers. Jolly says he wasn’t granted the same leeway given to white men of privilege.

To deal with that difference, Jolly says he always had liquid assets available in case loans were called in early, and he prepared a Plan B for loans that were denied.

“I know white people better than they know themselves. My survival in business depended on it,” Jolly says.

In his experience, there are many people in positions of power in the financial world “that don’t want minorities to exceed them.” In his view, these “friendly” gatekeepers seek to constrain a person of colour’s success.

“I managed to outsmart them, managed to stay ahead of the curve,” he says.

The plight of the poor

When asked what keeps him up at night, Jolly gets fired up. He cites the fact that so many people, in one of the richest countries in the world, don’t have access to basic needs: shelter, food and water.

Jolly decries “people freezing to death on the street” or Indigenous children without access to clean water, living in deplorable conditions.

“How do we sleep at night knowing this happens? And yet we have billions of dollars to do other things,” he says.

People may know him for his business ventures, but Jolly says that these days, his charitable deeds are a constant.

“I started a breakfast club at my ex-high school in Montego Bay, Jamaica. I do a lot of things but don’t broadcast it. I support a lot of people without them asking. I send regular cheques to people in the mail,” he says.

Lessons from 2020

Jolly says he and his family are taking the COVID-19 pandemic very seriously, because he belongs to a vulnerable demographic. He feels lucky to be able to shelter in place comfortably.

“I’ve learned to be thankful for small mercies and not get fixated on things you can’t change,” he says.

One thing that surprised him about this year was the groundswell of support, including that of Corporate Canada, for the Black Lives Matter movement. He says he was “quite taken and encouraged” by the collective “awakening” brought on in the wake of George Floyd’s death at the hands of police in the U.S.

But Jolly says he frets that much of what unfolded in recent months, and the grand proclamations by leaders in Corporate Canada haven’t resulted in lasting change.

“If you look around I don’t see a lot of changes that are commensurate with the concern that was manifested. If you look around Toronto, what institutional change has really happened around here?”

That prompted him to write a letter last month to Toronto Mayor John Tory, asking that the city move quickly to re-examine its approach to policing. Specifically, when it comes to mental health “wellness checks,” some of which have been captured on camera and show situations that have turned violent, even deadly. In Denham’s view, sending one or more uniformed police officers to perform these checks is a recipe for escalation.

At 85, Jolly says he’s not quite prepared to “stop opening my big mouth when it comes to human rights.”