Jun 4, 2024

Stock pickers defy Wall Street norm to risk it all on a few bets

, Bloomberg News

Nvidia to lead Wall Street higher after AI update

For active managers who spread out their bets across the world’s largest stock market, these are harsh times on Wall Street.

A historically small number of Big Tech firms keep driving equity indexes to new highs — in an era when cheap passive funds are grabbing billions of dollars in fresh capital and netting big gains by simply tracking the benchmark.

Now a cohort of stock pickers is turning to a high-risk strategy in a bid to outperform. They’re betting on a smaller and smaller number of lucrative companies across America, upending diversify-or-be-damned wisdom on Wall Street.

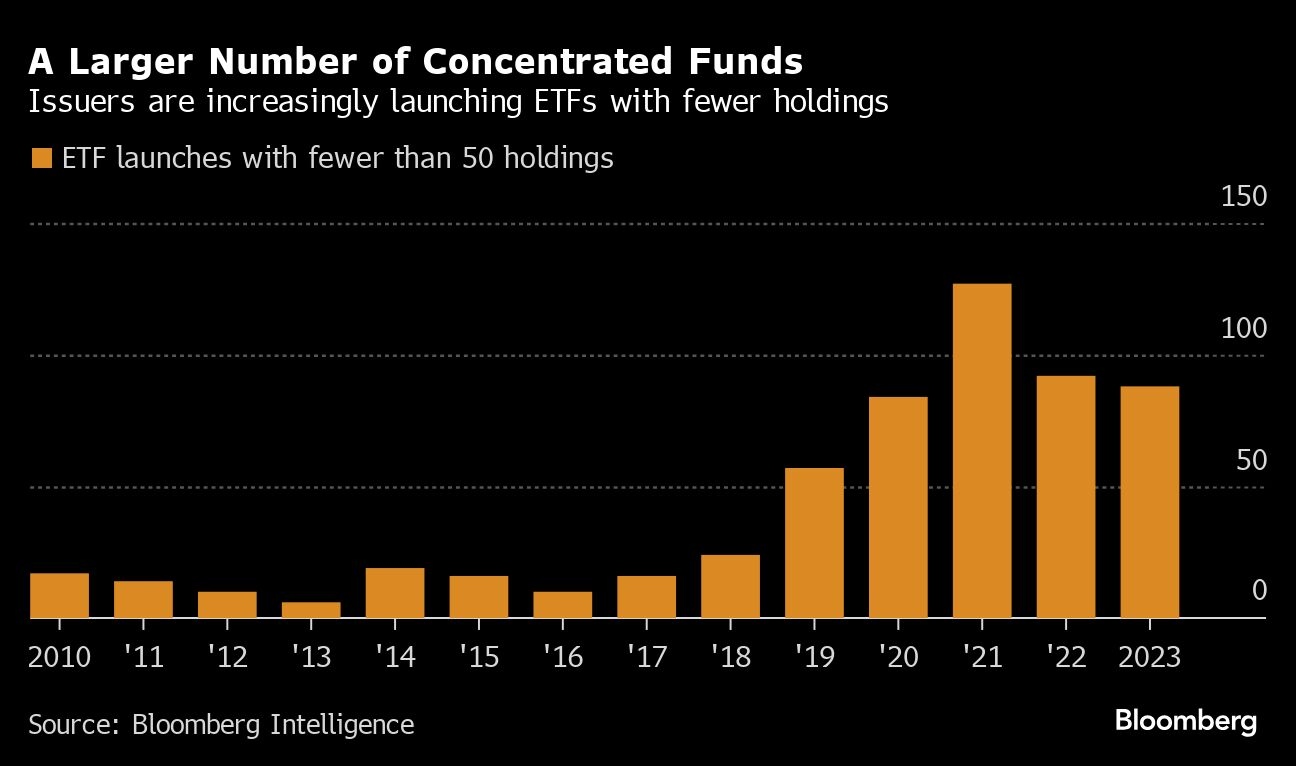

Consider this. Eighty-eight exchange-traded funds launched last year with fewer than 50 stocks, versus 19 debuts a year in the 2010s, data compiled by Bloomberg Intelligence’s Athanasios Psarofagis show. More broadly, the average number of holdings in new equity ETFs has shrunk to the least since 2010, at around 136 this year, per BI. It’s a similar story in mutual funds.

The thinking goes that lavishing money into a small group of carefully chosen equities will help these investors stand out in an era when gains in a historically narrow number of mega-cap firms has made beating indexes all but impossible.

It’s a gamble. Whittling down a portfolio can boost the odds of beating benchmarks by giving greater sway to favored picks that win big. Yet it worsens the consequences of being wrong, too. For managers convinced they have an edge, that’s a risk worth taking, says Nancy Tengler, who’s been running concentrated funds since the early 1990s.

“Portfolio managers do this all the time, especially less experienced ones: they over-diversify the portfolio and in doing that, they truncate the total return,” said Tengler, chief investment officer at Laffer Tengler Investments.

The Laffer Tengler Concentrated Equity Strategy — billed as holding just a dozen “best ideas” — speaks to the feast-and-famine performance, returning 39 per cent last year net of fees after a 25 per cent drop in 2022. Added together, the strategy’s annualized returns after fees are about 13 per cent on average since late 2019. That compares with about 11 per cent for the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

Smaller portfolios have gained converts at a time when the market is coughing up precious few stocks on which outperformance can be built. Only 27 per cent of the S&P 500’s constituents outpaced the underlying benchmark last year, making the goal of beating it harder, data compiled by Bank of America show.

Today, the index’s five largest stocks — Microsoft Corp., Apple Inc., Nvidia Corp., Amazon.com Inc. and Meta Platforms Inc. — make up more than a quarter of its value, and their influence is only growing. Enthusiasm over artificial intelligence combined with best-in-show earnings have built a seemingly insurmountable moat, driving the benchmark higher and bedeviling stockpickers.

While facts such as those might be reason to give up and hug the index for dear life, some fund managers are adopting the opposite approach: shrink down, and hitch fortunes to a shorter list of high-impact names. Bloomberg Intelligence data shows that over the last three years — via either skill or good luck — 35 per cent of the most-concentrated equity ETFs beat the S&P 500, compared with just 17 per cent of the least-concentrated group.

But while less diversification may improve the raw odds of rising above, the catch is that misses are more painful as well. The worst-performing high-concentration ETFs trailed by nearly 20 per cent in 2023, roughly double the laggards of the least-concentrated funds.

Count Morgan Stanley Investment Management’s Andrew Slimmon among those who sees a role for the high-conviction approach, as long as it’s implemented with care. Amping up the influence of key names — pushing up the portfolio’s “active share” in industry parlance — is what stock pickers are paid for, as well as being the main way way of demonstrating talent, he says.

“Over time, the higher your active share, the better managers do, because if you only own say 20 stocks, it’s going to become pretty apparent whether you’re good or not,” he said in an interview with Barry Ritholtz. “There is survivorship bias, but higher active share has proven to outperform lower active share over time.”

Far from a new concept, how a fund’s returns are affected by its weightings to specific stocks or sectors is among the most researched topic in money management, with a litany of terms like active share informing its principles. At its core, the research tries to disentangle the role of luck and skill in active investing, shedding light on whether any excess return is worth the fees and volatility.

Recent research shows that at longer time horizons, the market itself stacks the odds against anyone trying to locate alpha-generating winners reliably. Over the past century, the median 10-year return among the 3,000 largest U.S. stocks has lagged the broader benchmark by 7.9 percentage points, according to a 2023 paper by former New York University professor and quant manager Antti Petajisto.

“Concentrated stock positions are significantly more likely to underperform than to outperform the stock market as a whole over the long term,” wrote Petajisto, currently head of equities at Brooklyn Investment Group. “Trying to gamble on identifying those few stocks with outsized returns would be a bad idea.”

Just 26.4 per cent of U.S.-based mutual funds with under 50 holdings have outperformed over the past 10 years, according to data compiled by Bloomberg Intelligence’s David Cohne. Less-concentrated funds have fared better, but not by much: about 36 per cent have bested the benchmark over that time period.

But as with any data set, there will always be outliers — and that alone is enough to keep the dream alive for even the most down-on-their-luck stockpicker.

Arguably the most successful high-conviction portfolio is the Baron Partners Fund, which Wall Street veteran Ron Baron brought into existence in 1992. While unwavering faith in Elon Musk’s Tesla Inc. has bruised performance in 2024, the fund’s 21 holdings — several of which have been held for decades — have managed to outperform 98 per cent of peers over the past five years.

Listening to 81-year-old Baron describe his approach, it sounds simple: Find good companies and get to know their businesses better than virtually anyone else. It’s a process that takes a lot of questions, time and legwork but ultimately lowers turnover and can deliver better returns.

So why don’t more investors do that?

“Because they have great jobs, and they’re afraid if they don’t sell Tesla and the stock goes down, and Tommy down the street or Susan down the street sold it, they’re going to look smart. And he’s not going to look smart and he could get fired,” Baron said in an interview at his New York offices. “So people don’t want to take the risk. It’s also extra work, you have to know much more about the business than anyone else in order to keep holding it.”