Jun 15, 2024

Shanghai’s Solar Carnival Belies Fight for Survival in China’s Flagship Clean Energy Industry

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Visitors to the world’s biggest showcase of solar power could be forgiven for not realizing just how dismal conditions are in China’s flagship clean energy industry.

Hundreds of thousands of people descended on Shanghai’s largest convention center last week for the city’s annual solar gathering, where a carnival mood prevailed. They were met by company mascots dressed as pandas and astronauts, and presenters in ball gowns hosting wheels of fortune. There were booths serving popcorn, ice cream and cocktails, and video game competitions on massive screens rising toward cavernous ceilings.

Behind the scenes, executives were fretting over the crisis engulfing the sector. At home, prices have collapsed after a breakneck expansion created far too much capacity, forcing many firms to sell at a loss. Abroad, China’s dominance of the world’s supply chains is being tested by an explosion in protectionism. And the rapid uptake of solar power, the best story going in the fight against climate change, is now facing resistance as electricity grids chafe at handling a flood of energy available in the day that then disappears at night.

“We’re entering into a deep down-cycle,” Amy Song, vice president at solar material maker GCL Technology Holdings Ltd., said in an interview on Friday with Bloomberg TV. “Barely anyone is making money right now.”

Solar’s rise over the past two decades has been meteoric. The industry has grown from a niche sector for environmentalists to the planet’s dominant source of new energy. The world added 445 gigawatts of solar panels last year, more than all other power sources combined in any year of human history. Most of them were made in China.

That’s propelled the growth of multi-billion dollar companies, which are now comparable to the giants of oil and gas. But it’s also created the conditions that have bedeviled commodities markets through the ages. China’s solar companies have boomed, and now they’re heading for a bust that could eclipse earlier downturns in the industry’s fortunes.

A surge in demand that began three years ago boosted prices, unlocking ambitious expansion plans that have resulted in too much supply. Chinese companies ended 2023 with the ability to produce 1,154 gigawatts of solar modules — more than double the capacity at the close of 2021. Projected demand this year is just 585 gigawatts, according to BloombergNEF.

The rapid build-out is a typical tragedy of the commons.

Companies looked out for their own interests without considering the overall impact if all their rivals acted the same way, said Gao Jifan, chairman of Trina Solar Co, the world’s third-largest manufacturer of panels. They were helped along by local governments eager to meet their growth targets and banks hungry to make loans, he said.

Gao was one of several executives who called last week on the central government to intervene to help the industry get back on its feet. The menu of options presented included regulating which new factories can be built, cracking down on less-efficient facilities, capping price cuts, and promoting consolidation.

In the meantime, too many factories are bidding to supply too few projects, which has driven down prices to record lows. Recovery isn’t likely until 2025 or 2026, said BNEF analyst Youru Tan. Industry executives have warned that bankruptcies are in the offing.

Solar’s biggest backer is Beijing. The industry is one of the government’s ‘new productive forces’ that it hopes will allow the economy to pivot from decades of growth driven by the property market, low-end manufacturing and state-led investment. Other clean energy sectors like batteries and electric vehicles are in the same stable.

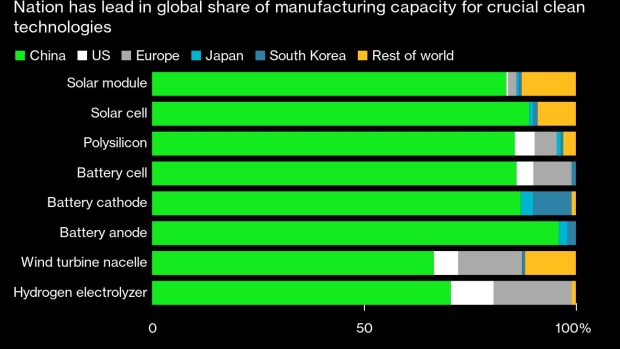

The government’s support, which in years past included generous subsidies, has helped deliver a world-beating industry. Chinese companies control more than 80% of capacity along every step of the supply chain. That’s rankled foreign governments, which don’t want to rely on a geopolitical rival for energy, and crave some of the industry’s jobs for their own people.

US President Joe Biden last month toughened trade measures against solar equipment from China, and his administration is now targeting operations in Southeast Asia, which are viewed as fronts that have allowed Chinese firms to bypass tariffs. India has also imposed import duties, and there have been calls in Europe to follow suit.

It’s left Chinese companies looking to invest overseas and win customers in nations that have put up trade barriers. That includes the US, after the Biden administration’s 2022 bill to provide incentives to boost domestic clean energy manufacturing.

Despite the dire outlook, there are reasons for optimism in the industry. Demand will continue to grow through the next decade, doing more than any other source to help the world decarbonize. And healthy profits from 2021 to 2023 mean many firms are sitting on large cash deposits to help them through the downturn.

But the issues faced by the industry are technical as well as commercial.

China installed a record 217 gigawatts of panels last year — more than has ever been built in the US — and solar now accounts for 22% of the country’s total generating capacity. But sunlight’s intermittency is straining the electricity grid.

Hundreds of small cities have halted approvals for new rooftop solar projects, and panels across the country are seeing their hours of usage reduced as the grid rejects their electricity because there’s not enough space for it during daylight hours. The government has recognised the problem, and recently loosened rules to allow installations in areas that otherwise have too much power.

Belt-Tightening

The broader solution is for grids around the world to build more power lines that can transfer excess clean power to where it’s needed. More storage, mainly via batteries, is also required. But adding those costs means solar power will need to keep getting cheaper.

For now, the industry is focused on belt-tightening. Longi Green Energy Technology Co., once the world’s most valuable solar manufacturer, announced earlier this year it would lay off thousands of workers. Others have halted production. Smaller producers are being forced to delist their shares from stock exchanges.

Wuxi Suntech Power Co. Chairman Wu Fei likened China’s solar sector to the home appliance makers of 15 years ago, when 300 or so companies vied to sell washing machines, fridges and air conditioners across the country. That industry has consolidated to just a handful of players, he said, and solar will likely follow suit.

“Today’s photovoltaic reshuffle has just begun,” he said. “The second half of the year will be even worse.”

Listen on Zero: The Godfather of Solar Predicts its Future

--With assistance from Kathy Chen, David Ingles and Annabelle Droulers.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.