Aug 5, 2021

No, team Biden, carmakers' chip crisis isn't getting any better

, Bloomberg News

Look to semiconductor, telecom stocks for opportunity in China amid crackdown: Larry Shover

In late July, U.S. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo said things were getting better for automakers suffering chip shortages that have shuttered plants and crippled production.

Not that much better, it turns out. This week, suppliers of those vital electronic components warned the problem is far from over and said the car industry’s rapid pivot to electric vehicles may further stretch their ability to catch up. Their customers share the cautious view.

According to the two biggest makers of chips used by automakers, Infineon Technologies AG and NXP Semiconductors NV, supply and demand won’t come into balance until the middle of next year. That would mean prolonged pain for carmakers that have been grappling with the issue since late 2020.

“It’s really important to stress how much we’re increasing supply,” NXP Chief Executive Officer Kurt Sievers said in an interview. “Demand is still outstripping supply,” and the tightness will last into 2022, he said.

Chipmakers have little to complain about -- surging revenue has pushed their profits to record levels. But auto dealerships have been left with empty lots, preventing car manufacturers from fully capitalizing on a post-COVID increase in demand. The protracted uncertainties are on course to cost carmakers at least US$110 billion in lost sales this year.

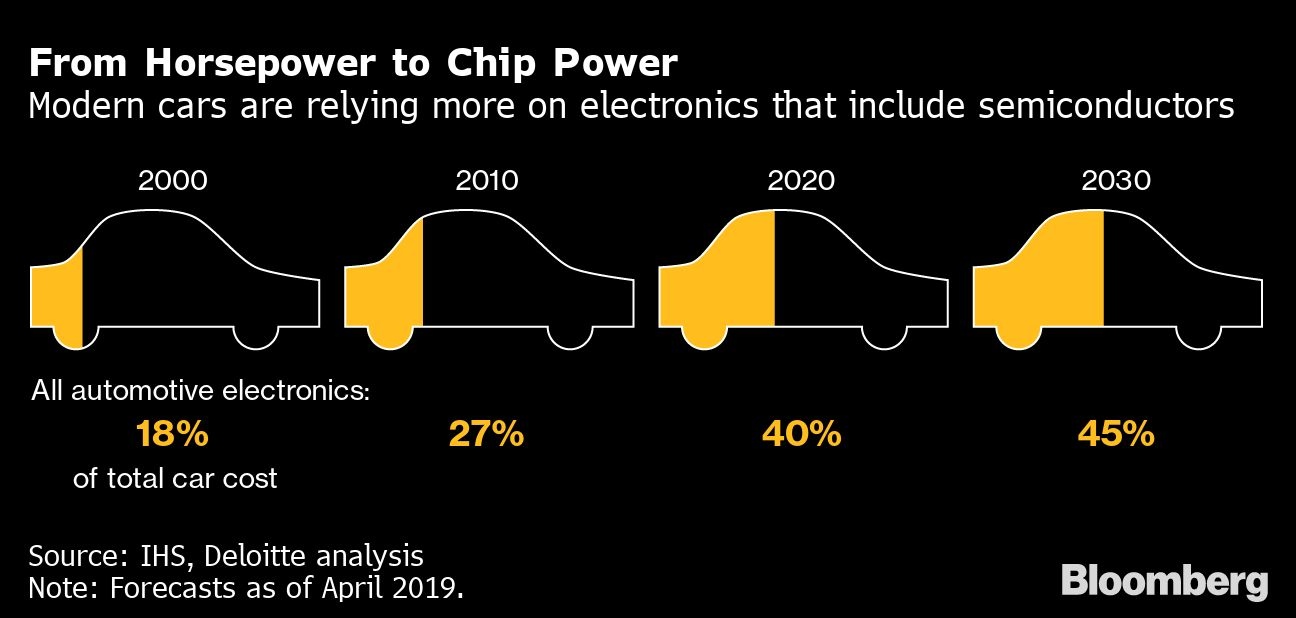

The shortage also threatens to slow the shift to electric vehicles. Auto brands have announced a flood of new EVs this year, with even gas-engine icons such as Ford Motor Co.’s F-150 pickup truck getting electric versions. The batteries, electric motors and systems that monitor and control EVs are based on semiconductors. New entertainment, safety, and driver-assistance features also rely on chips.

The net effect is that there are a lot more semiconductors in a car than ever before.

Illustrating that, NXP’s auto-chip sales jumped 21 per cent in the first half compared with the same period in 2019, before the pandemic. That happened even as global car production fell 13 per cent, according to Sievers. Semiconductor content in EVs, including hybrids, is twice that in a gas-powered car, he said. In 2022, EVs will account for about a quarter of car production, double the 12 per cent share they had in 2020.

It takes months for chipmakers to boost output, or two years if they build a new plant that costs billions of dollars. Meanwhile, the coronavirus pandemic is still causing production disruptions.

The vast majority of chips used in vehicles are made using older production technology. The industry hasn’t invested in such manufacturing because it’s closer to obsolescence and less lucrative than chips that go into the latest smartphones and computers. Still, a number of factories planned or underway are set to bring relief, albeit not anytime soon.

“It’ll take 12 to 18 months for those fabs to come on line,” said Syed Alam, the head of Accenture Plc’s semiconductor practice. “Silicon in automotive has been increasing rapidly. Electric vehicles take it to a different level.”

On Wednesday, General Motors Co. CEO Mary Barra called the component supply situation “fluid.” Constraints may continue to weigh on profitability, the company cautioned. Barra said GM has just 25 days of inventory in the U.S., about one-third of its normal stock of cars and trucks. It has prioritized its highest-margin vehicles, but hasn’t been able to shield them entirely from the shortages.

Volkswagen AG last week cut its full-year delivery forecast on chip supply problems, saying disruptions and bottlenecks have intesified throughout the industry. BMW AG characterized semiconductors as a cloud on the horizon and said it expects to lose sales of about 90,000 cars in 2021, equivalent to less than 10 per cent of first-half shipments.

“The longer the supply bottlenecks last, the more tense the situation is likely to become,” Nicolas Peter, BMW’s finance chief, said in a statement this week. “We expect production restrictions to continue in the second half of the year and hence a corresponding impact on sales volumes.”

Ford is closing or curtailing production at eight factories this month, including the plant manufacturing its new version of the iconic Bronco sport utility vehicle. Five of GM’s North American plants will experience “downtime” due to “semiconductor production adjustments” in August, according to spokesman David Barnas.

Ford and Stellantis NV raised their profitability outlook for the full year, but that’s because they are saving scarce chips for higher-end vehicles rather than mass-market models. That helps to boost average prices, while total sales volumes are getting hit.

China’s biggest automaker SAIC Motor Corp. cut its output by 500,000 cars in the first half because of the shortage, while the country’s government this week launched a probe into possible price manipulation of auto chips.

In Japan, Toyota Motor Corp. maintained its full-year forecast on Wednesday on chip shortages and the pandemic, disappointing investors who were looking for a boost. Honda Motor Co. cut its full-year unit sales target on tight semiconductor supply.

Korea’s Hyundai Motor Co. warned in late July the chip crunch could reduce its third-quarter deliveries after posting its biggest profit in seven years, bolstered by sales of luxury Genesis cars and Ioniq 5 electric vehicles.

Chipmakers say supply constraints persist at foundries, the manufacturers that they rely on for some of their production. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., the go-to foundry for major auto-chip makers, plans to boost output of automotive microcontrollers by 60 per cent from 2020 levels, which NXP’s Sievers told analysts this week “isn’t that much.” In total, TSMC is spending US$100 billion to expand manufacturing over three years.

“Inventories are extremely tight and end demand is being postponed,” Infineon CEO Reinhard Ploss said on a conference call this week. “All in all, it will take time to get back to a supply demand equilibrium. In our view, this will take until well into 2022.”