Jun 26, 2024

China’s EV Success Story Built on Price Wars, Tesla Factor

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- China became a world leader in electric vehicles by showering companies with public cash. It’s a charge increasingly heard in the US and Europe, and a refrain that’s central to the escalating trade war.

If it were only that simple, China would have champions in every industry, from aircraft to semiconductors. The unique rise of China’s EV makers, which are rapidly taking over the world despite Western politicians’ efforts to block them, holds lessons for other countries about how industrial policy can succeed.

While Beijing plowed in plenty of money after identifying EVs as crucial for the environment and the economy, to a large degree it was a foreign company that kickstarted the domestic industry — an argument against the protectionism that China has insisted on in many other sectors. Although former government minister Wan Gang pushed the country early on to leapfrog the dominance of foreign brands by investing in electric cars, when Tesla Inc. started manufacturing locally in China in 2019, it sparked genuine enthusiasm among consumers and fueled the build-out of an entire EV supply chain.

Innovation became the catch cry and scores of EV makers blossomed, each trying to outdo the other on design, software and other high-tech features. Many fell by the wayside, leaving survivors leaner and hungrier. In 2024, China’s EV market is characterized by bruising price wars and intense competition.

The policies employed by China’s leaders are now being emulated by Western governments, which are trying to make their own EV makers more competitive, including with subsidies. Yet it’s clear that Beijing’s willingness to let companies fail while boosting the overall new-energy vehicle sector is what’s made a difference. In contrast, its decades-long commitment to manufacturing homegrown aircraft to take on Boeing Co. and Airbus SE hasn’t seen Commercial Aircraft Corp of China Ltd. make many viable inroads into that global duopoly.

In EVs, China hasn’t sought to “create specific national champions,” said Gerard DiPippo, a senior geo-economics analyst at Bloomberg Economics. “It wanted winners but didn’t want to pick them. It was more of a ‘let one hundred EV makers bloom’ approach.”

That strategy has seen carmakers like BYD Co. offer electric hatchbacks that have rotating touchscreens from just 73,800 yuan ($10,200). Li Auto Inc.’s L-Series has rocketed to the top of electric SUV charts thanks to its spacious interiors and top notch in-car entertainment. While Apple Inc. gave up on its EV project, Xiaomi Corp. founder Lei Jun has fans queuing up to buy the smartphone maker’s recently released SU7 EV.

Some of these automakers may even have a shot at becoming the next Toyota Motor Corp. — BYD, which produced more than 3 million cars last year, overtook Tesla in the fourth quarter as the world’s largest seller of EVs — and China’s economy is getting a lift at the same time.

Innovation in EVs has also rippled into surrounding areas, including batteries and supply-chain optimization.

The government effectively excluded foreign battery manufacturers from the market for a time when the industry was still developing, creating a “whitelist” of approved cell makers that could supply local EV manufacturers. But the list was abolished in 2019 and in the first four months of 2024, BYD and Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Ltd., or CATL, had a combined global EV battery market share of 53.1%, according to Seoul-based SNE Research. And at a recent press briefing, a Commerce Ministry official boasted that electric carmakers in the Yangtze River Delta near Shanghai can get all the parts they need within a four-hour window.

With China’s government having called time on growth driven by real estate and infrastructure, the EV industry is delivering. It’s on track to contribute 2.7% of gross domestic product by 2026, Bloomberg Economics estimates. That’s nine times as much as in 2020, although still not enough to fill the gap left by China’s burst housing bubble.

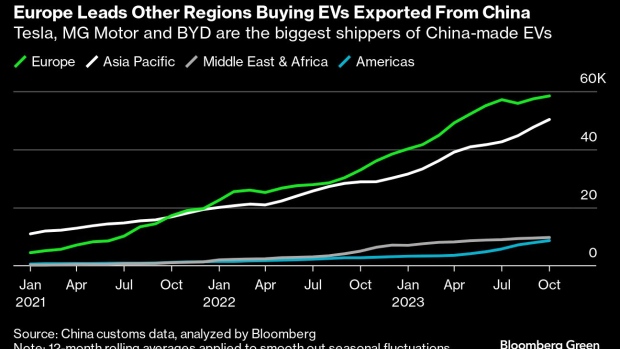

Longer term, automakers could contribute even more — but there are obstacles to their global advance. US tariffs of 100% effectively shut them out of that market and the European Union this month announced plans that take duties as high as 48%. Both have cited Beijing’s financial backing for the industry and the overcapacity it’s encouraged.

It would be a mistake however for Western policymakers to conclude that subsidies are a magic bullet, Yale Zhang, managing director at Shanghai-based consultancy AutoForesight, said.

Subsidies alone “never create a healthy industry,” he said. “The reason for China’s success is more product driven and demand driven.” After the US led the way with Tesla, “China ran faster and the Europeans slowed down,” he said.

Running faster can take a toll. Chinese brands are under constant pressure to refresh and upgrade, sometimes as often as every 18 to 24 months — a rate unthinkable elsewhere. In Europe, it might be more like every four to five years. The frenetic pace can leave employees burned out.

‘Stark Contrast’

China’s need to bring down heavy pollution in cities played a crucial role in its EV policy. Generous subsidies went to buyers to incentivize them to switch to electric cars, creating a demand-led cycle rather than a supply glut.

“The government came in at a time when the EV industry was still quite young, so there wasn’t a lot of competition,” Ilaria Mazzocco, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said. “But it was mature enough to actually be able to make very rapid progress.”

That’s in “stark contrast” to the US, which preferred to let market forces determine whether EVs would become a viable alternative, according to Paul Triolo, a former US government official who specializes in China and technology policy at Albright Stonebridge Group.

China managed to create “an air of inevitability” around the uptake of EVs, he said. “Beijing’s approach was to provide sustained subsidies, encourage private sector players to jump in and compete and then gradually withdraw support as the most innovative and capable private sector players emerged from the fray.”

China’s helping hand ranged from investment in charging infrastructure — even when the number of EVs on the roads was minuscule — to introducing preferential license-plate policies.

Asia’s biggest economy has also become especially strong in batteries, the biggest reason why its EV firms have a cost edge over rivals, Herbert Crowther, an analyst at Eurasia Group, said.

“Chinese battery firms are reaching price levels that are surprising to even the biggest foreign competitors and which could completely change the traditional economics of EV input costs,” he said. That success stems from programs to secure supplies of the raw materials needed in EV cells, an area where “Chinese policy is also effective and where Western industrial policy will probably continue to struggle.”

Future leaps forward for China could come in any number of areas, from AI to renewable energy or bio-pharmaceuticals. Ultimately, it will be up to the nation’s scientists and entrepreneurs — not officials — to make things happen.

Winners will be made by “governments that create an environment for innovation,” Scott Kennedy, a China specialist at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said. That will allow “the potential for breakthroughs by companies to eventually find a place in the market.”

--With assistance from Linda Lew, Chunying Zhang, James Mayger and Danny Lee.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.