Aug 9, 2022

US States Slash Taxes Most in Decades on Big Budget Surpluses

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- More than half of US states are using record budget surpluses to fund their biggest collective tax break in decades, risking future revenue shortfalls to help residents combat inflation and make some long-sought cuts.

Almost two dozen states slashed personal or corporate income-tax rates in the past two years and more than a dozen enacted temporary relief in 2022. Democratic governors often opted for tax holidays and one-time rebates, while many Republican leaders cut rates for good, usually for the highest brackets.

Those changes amount to $15 billion in total cuts for fiscal year 2023, according to a survey of governors’ proposals by the National Association of State Budget Officers, which said the plans if enacted as is would produce the largest reduction in revenues since the survey began in 1979. While higher-than-forecast tax collections and a massive influx of federal pandemic aid have left states flush with cash, analysts warn that permanent tax cuts could cause financial problems as the economy slows and inflation persists.

“Both parties have now kind of gotten on the bandwagon, and the revenue picture for the moment supports it,” Michael D’Arcy, director of US public finance at Fitch Ratings, said of the tax-reduction spree. “The question is: What will the longer term shake out be?”

Widespread tax breaks in the nation’s statehouses stands in contrast to what’s happening in Washington, where the Federal Reserve is trying to tamp down inflation by raising interest rates to pull money out of the economy. The US Senate on Sunday passed a new minimum tax on corporations and a levy on stock buybacks, both part of a plan to spend $437 billion over a decade on incentives for renewable energy projects and electric vehicle sales.

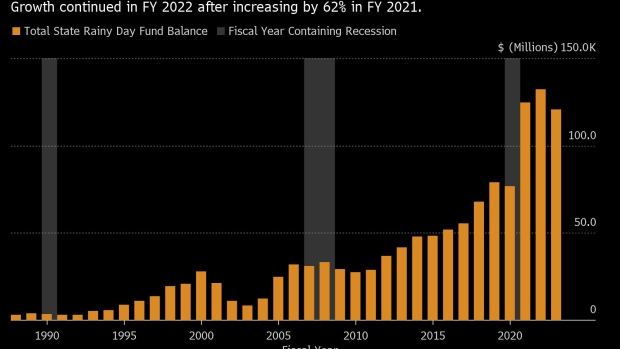

The state-level largesse is being financed by a broad-based jump in tax collections in the wake of the pandemic. General fund revenues in the last fiscal year soared higher than expected in 49 states, according to the NASBO report, and many are coming off a strong decade of padding their rainy day funds.

Florida, for example, ended FY 2022 with a record $21.8 billion surplus, the governor’s office announced in July. Kentucky reported 14.6% growth -- the highest rate in three decades -- and its second-highest surplus ever, surpassed only by FY 2021.

“States are better prepared to weather the next five years than they’ve ever been prepared to weather a downturn in history,” said NASBO executive director Shelby Kerns at an Urban Institute panel last month.

Some analysts caution that swelling revenues are the result of temporary distortions: record stock market performance in 2021 drove up income-tax collections, and federal stimulus money spurred consumer spending while providing state and local governments with hundreds of billions of dollars in aid. While the picture remains strong for now, there are already signs the golden era of state fiscal health may be ending.

California is likely to see revenue from its three major tax sources fall short of forecasts this fiscal year, according to a post last week by Deputy Legislative Analyst Brian Uhler. At the local level, New York City’s estimated personal income-tax payments in June declined to the lowest level since 2017.

Temporary or permanent?

In the last two years, 21 states permanently cut personal or corporate income-tax rates, according to the Tax Foundation, and at least three others have called special sessions on tax cuts or will put the issue before voters this November. More than two-thirds of those states are led by Republican governors.

The vast majority of states that cut individual income taxes did so at the top: consolidating the highest brackets, decreasing the top marginal rate, or both. Several implemented or reduced an existing flat rate.

Only New York and Wisconsin -- both led by Democratic governors -- targeted lower or middle-income brackets. Many of the permanent changes will be phased in over several years, and some have guardrails that prevent cuts from taking effect if revenues or rainy day fund balances are too low.

Still, the biggest cuts are “likely to necessitate difficult budget choices in the future,” Fitch warned in October. And most states, said Lucy Dadayan, a senior researcher at the Urban Institute, haven’t announced a plan to offset the lost tax collections.

Among states offering temporary tax relief, five paused gas taxes, four suspended sales taxes on groceries and five called a holiday on many or all sales taxes at some point this year, with the measures evenly split among red and blue governors’ offices. A handful made those sales tax changes permanent.

Taxpayers in seven Democratic states and four Republican ones are set to receive one-time rebates, with another rebate in Massachusetts potentially on the horizon. Some states, like California, will send more money to lower-income households; others, like Georgia, are issuing flat rebates to all eligible taxpayers.

One-time injections have a limited impact on state budgets, Fitch’s D’Arcy said. But they also have a limited benefit for recipients, said Dadayan and Timothy Vermeer, an analyst at the conservative-leaning Tax Foundation.

A gas tax holiday, for example, may help a family save just $40 a month. A targeted rebate program would be more “prudent” to assist low-income families hit hardest by the pandemic, Dadayan said. Vermeer emphasized that permanent cuts yield longer and larger dividends.

Stimulus and surpluses

While stimulus from Washington helped drive budget surpluses, the US aid can’t be used for tax cuts. Many Republican states are pushing back on that Treasury Department restriction in court, and rulings have so far been overwhelmingly in their favor. In the meantime, state budget officials insist that tax reform is born out of record revenue collections rather than federal aid.

“Absolutely no ARPA (American Rescue Plan Act of 2021) funds will be used to directly offset the potential tax cuts,” Arkansas Budget Officer Robert Brech wrote in a memo to the state’s governor last month about a proposal to accelerate personal and corporate income tax cuts passed in December. “Any indirect offset would be difficult to compute, if it exists.”

While states have not fully complied with federal restrictions on aid spending, Dadayan said, it’s difficult to pin down exactly where a given funding increase may have come from given the degree of excess liquidity in the past two years. The tax cuts, she added, “would have happened regardless” of aid.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.