Sep 8, 2021

Trudeau has 12 days to salvage his career after election blunder

, Bloomberg News

Party leaders must decide how they'll control spending and pay off debt: PM Harper's former campaign manager

Last month, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was convinced of two things: his successful vaccination strategy had made Canadian voters grateful, and his main opponent, Conservative Leader Erin O’Toole, was somewhere between unpopular and unknown.

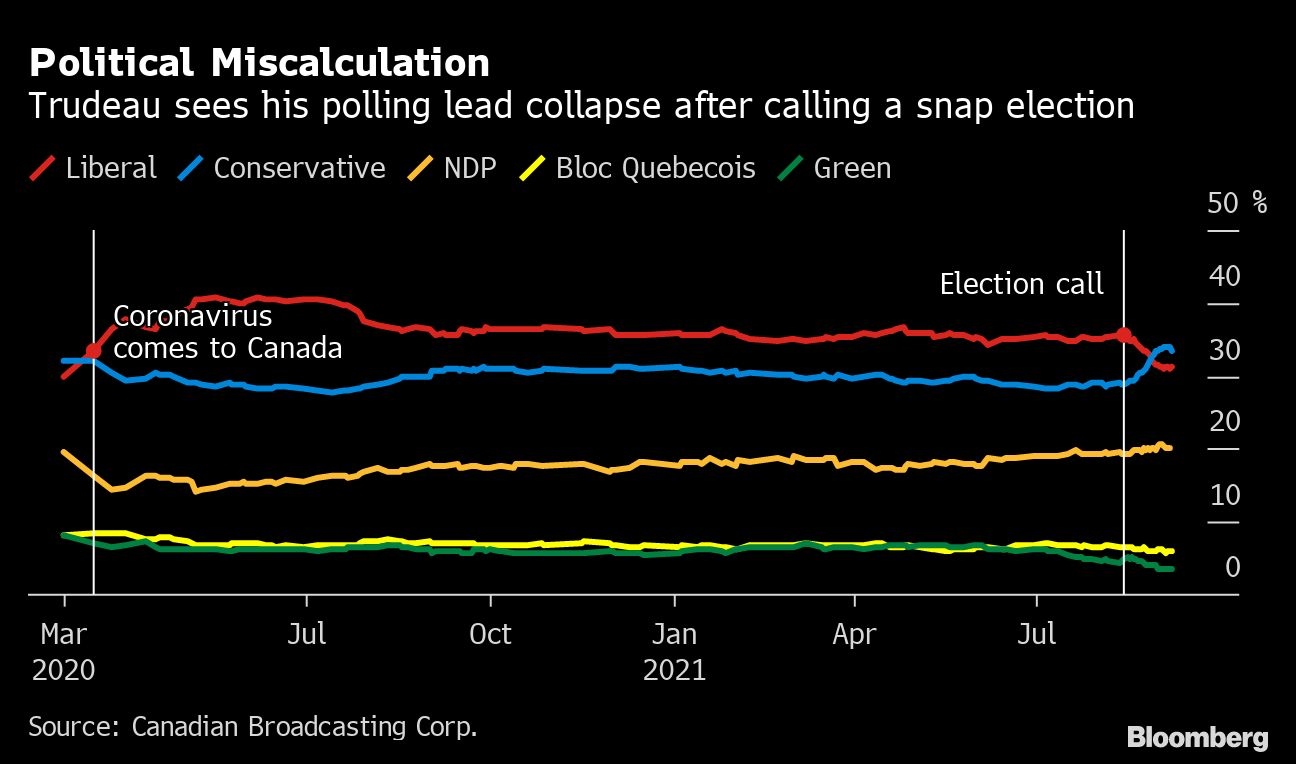

So Trudeau called a snap election for Sept. 20, hoping to earn his Liberal Party a ruling majority. Instead, his numbers dropped instantly, confounding many. With 12 days to go, he’s likely to end with a weakened minority government or even a humiliating defeat.

“The Liberals likely called the election thinking that they would be able to run on their pandemic record, bask in a vaccination halo and get ahead of the post-stimulus economic adjustment,” said Nik Nanos, an Ottawa-based pollster at Nanos Research Group. “That’s out the door now.”

Analysts suspect a number of factors are at play in Trudeau’s potential downfall.

Many start with the mood of the electorate. They say voters feel taken advantage of by a politician seen to have turned a health crisis into a power grab. In one poll, nearly 60 per cent said the country shouldn’t be having an election. Canadians are comfortable with a minority government and have no special desire to help the Liberals gain full parliamentary control.

Others point to tactical factors: On day one, Trudeau struggled to convey a clear message about his vision and the reason for the vote. On day two, O’Toole’s Conservatives released a platform focused on the economy and free of much of the party’s traditional ideological baggage.

After Trudeau’s lead evaporated, the Liberals started focusing on wedge issues -- abortion, private health care, anti-vaxxers and gun control -- aimed at painting the Conservatives as regressive. The Tory leader hasn’t taken the bait.

Frustrated Liberals talk about an exhausted group of insiders burned out by the pandemic. They say the government has failed to replenish itself with new talent and yet came to the election with excessive self-confidence that led them to believe in the inevitability of victory.

“I don’t understand how they could have been so tone-deaf about the mood of the Canadian public, about peoples’ total preoccupation with COVID and some kind of return to normal,” said Peter Donolo, a vice chairman at Hill+Knowlton Canada who was communications chief to former Liberal Prime Minister Jean Chretien.

There are stories of Liberal officials returning from vacation only days before the start of the campaign, and local candidates short of volunteers.

There were also gaffes. Trudeau said he doesn’t think of monetary policy as a top priority on the day Statistics Canada reported the highest inflation since 2011 -- a clip Conservatives are now using in attack ads about the cost of living. In another embarrassing development, Twitter reprimanded Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland for publishing a doctored video of O’Toole speaking about private health care.

O’Toole did better than expected. His platform calls for an interventionist, pro-labor and big spending program that Conservatives haven’t offered up in decades, in the hopes they can broaden their voter base.

It’s also true that while Trudeau handled the pandemic well, for many voters there remains about him a sense that style outweighs substance, that he enjoys his fame a little too much in a land where good sense and modesty are prized over sex appeal.

Still, it’s too early to write off Justin Trudeau.

His slide has leveled off and media scrutiny is now turning from the Liberals to the Conservatives. There are also signs that one Liberal wedge issue -- over whether O’Toole would loosen a ban on assault-style firearms -- is gaining traction.

With party loyalty relatively low, swings of momentum can occur until the final days. The campaign’s only English-language debate Thursday night could also prove pivotal.

In past elections, Trudeau has proved a formidable campaigner. In 2015, he catapulted from third place to victory in large measure on an image as a happy warrior conveying a more hopeful future -- what he called “sunny ways.”

In 2019, he overcame revelations that he wore blackface more than once before entering politics -- what would have been career-ending news for most politicians. Trudeau lost his majority in parliament and the popular vote, but held on to key urban voting groups to secure a stable government with support from smaller parties.

The difference this time is the focus is more on the core competencies of a leader who has been in power for six years and whose second term has been dominated by the pandemic. “The country is grouchy and wants someone to tell them when normal comes back,” said Chad Rogers, a Conservative adviser and founding partner at Crestview Strategy.

In polling released by Abacus Data over the weekend, 71 per cent of Canadians say they would prefer a change in government -- almost identical to numbers in the days leading up to the election in October 2019.

Trudeau clung to power, barely. That may be as good as it gets two years later. It also may be enough.

“If after an election you are in government, that’s a win,” said Tim Murphy, who was chief of staff to former Liberal Prime Minister Paul Martin. “If that’s a minority, it’s a minority, but you are still in government.”