Aug 8, 2022

Top China Strategist Sees Stocks in Limbo as GDP Growth Slows to 2%

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Don’t get too excited about prospects for a rebound in Chinese stocks. That’s the advice of an influential market strategist who says the nation’s equities will continue to struggle as economic growth slows and Beijing’s relationship with Washington worsens.

Hao Hong, who was ranked the No. 1 China strategist by Asiamoney in 2017 and 2018, said it would be very optimistic to expect China’s economy to grow even at an annual rate of 2% over the next 10 years as the once-hot property sector cools off. The ongoing political tension with the US, especially the threatened delisting of Chinese stocks from US exchanges, is another overwhelming force that will pressure equities both on the mainland and in Hong Kong, he added.

“Don’t expect any record highs anymore,” Hong said during an interview with Bloomberg News while on vacation in New York last week. Stock markets in mainland China and Hong Kong “will have much difficulty breaking out of their trading ranges.”

Hong, who is based in Hong Kong, left Bocom International Holdings as chief strategist in early May and declined to discuss the circumstances surrounding his departure. His pessimistic outlook for Chinese growth stands in contrast to the consensus of economists. While housing market troubles and the Zero Covid policy have caused Beijing to virtually give up on a target of about 5.5% economic growth this year, the median forecast of economists surveyed by Bloomberg calls for growth of 5.2% next year and 5% in 2024.

“Nobody can see what the new growth engine is or where to invest in,” the analyst said. “Industries such as new energy or semiconductors could help lift growth, yet their contributions are just not enough to compensate for losses from the plunging property sector.”

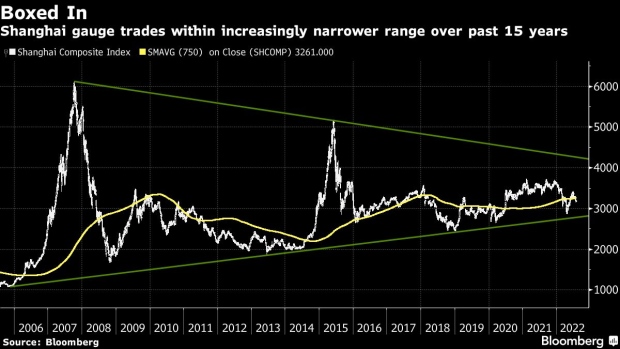

The Chinese economy grew at an average rate of 5.4% between 2019 and 2021. If growth were to decelerate to 2%, that would potentially further squeeze equity valuations. Over the past 15 years, China’s stocks have already suffered from falling multiples even as earnings kept rising. As a result, prices have been stuck within tight ranges.

Hong pointed out that the Shanghai Composite Index has traded within an increasingly tighter range over the past 15 years. Its 750-day moving average, which captures the market’s ups and downs over the previous three-year period, peaked in early 2010 and has failed to set new highs ever since. The same is true of Hong Kong’s Hang Seng China Enterprise Index. Things will probably get worse, Hong warned.

“The growth model determines how high stock markets can go,” Hong said. “Just like a jumbo jet cannot take off on short runways.”

Hong’s predictions about the Chinese market have proven accurate in the past, helping him build a reputation as an objective strategist worth following. He maintains a very active profile on Twitter, where he writes in both Chinese and English to almost 84,000 followers. One prescient call came on June 16, 2015, when he told Bloomberg Television that China’s surging equities were in a bubble and the chances of a market crash were increasing. The Shanghai Composite Index went on to lose about half its value by the time it set a four-year low in early 2019.

Property Addiction

Hong’s main concern at the moment is China’s too-big-to-fail property sector. Construction and property sales have been the biggest engines of economic growth since President Xi Jinping came to power a decade ago. Home prices skyrocketed — surging sixfold over the past 15 years — as an emerging middle class flocked to property as one of the few safe investments available. The relationship between the real-estate sector and China’s gross-domestic-product growth strengthened over the past dozen years, with a “significant link” emerging after 2010, the Bank for International Settlements said in its 2022 annual economic report.

Yet chaos in the housing market this year, including mass boycotts of mortgage payments from buyers who have yet to see homes completed by struggling developers, has triggered state intervention to fend off greater damage to China’s financial system. China may allow homeowners to temporarily halt mortgage payments on stalled projects without incurring penalties, people familiar with the matter told Bloomberg last month, as authorities race to prevent the crisis from upending the world’s second-largest economy.

Hong believes Beijing should have started to deal with the housing problems a decade ago.

“Now it’s too late,” he said. “Policy makers can’t make up their mind to abandon the real estate-driven growth model until some new one emerges.”

Chinese ADRs

Another risk, according to Hong, is the fact that Chinese companies whose stocks are trading in the US have become a flash point between Beijing and Washington. US Securities and Exchange Commission Chair Gary Gensler said last month that officials in the two countries must reach an agreement “very soon” over access to audit work papers for Chinese companies to avoid being kicked off American exchanges.

Hong believes delistings from US exchanges are inevitable, which will weigh significantly on both mainland and Hong Kong markets from next year onward.

“Hong Kong indexes will fall further with so many firms going home,” he said. “The pool is simply not big enough to absorb them all.”

The mainland market will be impacted as well. As the US-listed companies return home, Beijing will have to expand the stock-connect programs with Hong Kong, essentially allowing more mainland money into the city to offset the extra supply of shares. “This will only drive down A shares,” Hong said. “It’s going to be a lose-lose scenario for both Chinese companies and investors because good firms can’t get priced decently.”

In his opinion, the agriculture, new-energy and semiconductor sectors could benefit from China-US decoupling, as they will be heavily supported by government policies. However, Hong doesn’t recommend those stocks. Increased centralization of economic and political control, stronger state-owned enterprises and a weaker private sector, along with Beijing’s push for so-called “common prosperity,” will lead to a shrinking role for financial markets in the economy, according to the strategist.

“Beijing isn’t necessarily willing to share gains with private investors,” he explained, “These industries will be dominated by state-owned enterprises and private investors may only have the opportunities to buy their bonds.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.