Jun 7, 2023

The Road to Modi’s Ambitious Make-in-India Goal Runs Through China

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Fun Zoo Toys is an Indian manufacturing success story. The maker of heart-shaped cushions and “Little Ganesha” dolls started out as a family business in 1979 and has grown to be one of the nation’s major manufacturers of fluffy toys.

Sales doubled after Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Made-in-India push saw import duties on toys ramped up from 20% to 70% over three years to 2023. But that’s just half of the story: the production surge to meet those sales wouldn’t have been possible without raw materials like metallic pins, integrated circuits and LEDs imported from China.

“We have just introduced electronic toys and the challenge we are facing is that mini toy motors used in that are not being made here,” says Naresh Kumar Gupta who runs the company near New Delhi with his wife Santosh Gupta. “Making metallic pins which are fixed along with the gears and motors to make the rotations is a challenge here.”

It’s a Catch-22 that ensnares companies in India making everything from a baby’s first toy to mobile phones: the more they try to ramp up production in competition with China, the more dependent they become on their northern neighbor for components and raw materials.

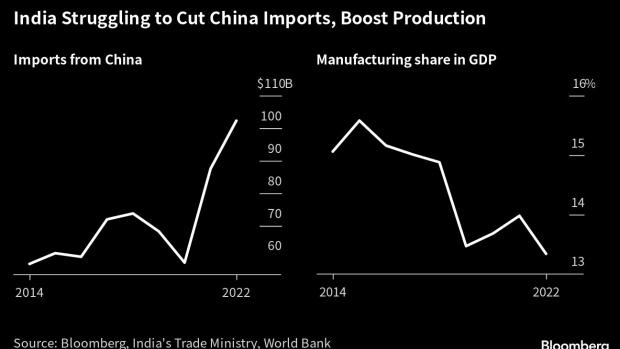

India’s imports from China stood at $102 billion in 2022, nearly double what it buys from its next two biggest markets — the United Arab Emirates and the US — combined. And the share of manufacturing in India’s GDP has dropped to about 13%, from 16% in 2015, and is still well below Modi’s 25% goal — the target for which has been pushed back three times to 2025 now.

Click here for the latest Stephanomics Podcast

Along with protectionist policies, the Modi administration has introduced production-linked financial incentives for sectors such as electronics and automobiles. And the $24 billion subsidy program is showing some successes, with companies such as Apple Inc. and Samsung Electronics Co. expanding.

Yet even with those headline-grabbing wins, the jury is still out on whether India can make a dent in China’s manufacturing dominance. Former Reserve Bank of India Governor Raghuram Rajan says such incentives are largely being used by companies that are assembling in India, rather than actually making stuff, leaving the nation even more dependent on imported components and raw materials.

“We certainly cannot claim the rise in exports of finished cell phones is evidence of India’s prowess in manufacturing,” Rajan wrote in a recent paper with two other economists. “Indeed, a key question is whether the 6% subsidy India pays on the finished mobile phone, coupled with state subsidies, actually outweighs the value added in India.”

A government spokesman didn’t respond to an email and a text message seeking comments.

Biswajit Dhar, a professor of economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, says taking China’s mantle as ‘Factory to the World’ won’t be easy, despite the fact that many companies are looking to diversify their supply chains due to geopolitical tensions. That’s because China is so deeply entrenched in global supply chains, whereas India suffers from layers of red tape, inefficient workers and low innovation in manufacturing industries.

“Getting hooked off China won’t happen because downstream industry is always going to prefer cheap imports that are coming in. It’s pure economics,” said Dhar. “What China offers to companies, India can’t at this stage.”

Ajay Sahai, director general and chief executive officer of exporters lobby the Federation of Indian Export Organizations, is confident India will be able to ramp up its manufacturing capabilities, but acknowledges it’ll need imports to do so.

“I have the choice either to cut down my finished goods imports or raw material imports,” Sahai said. “We have taken a choice that initially we will focus on finished goods.”

--With assistance from Adrija Chatterjee and Sankalp Phartiyal.

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.