Jun 11, 2021

Powell gets Wall Street buying view that inflation won't last

, Bloomberg News

Posen Says U.S. Economy Is in 'Very Good Shape'

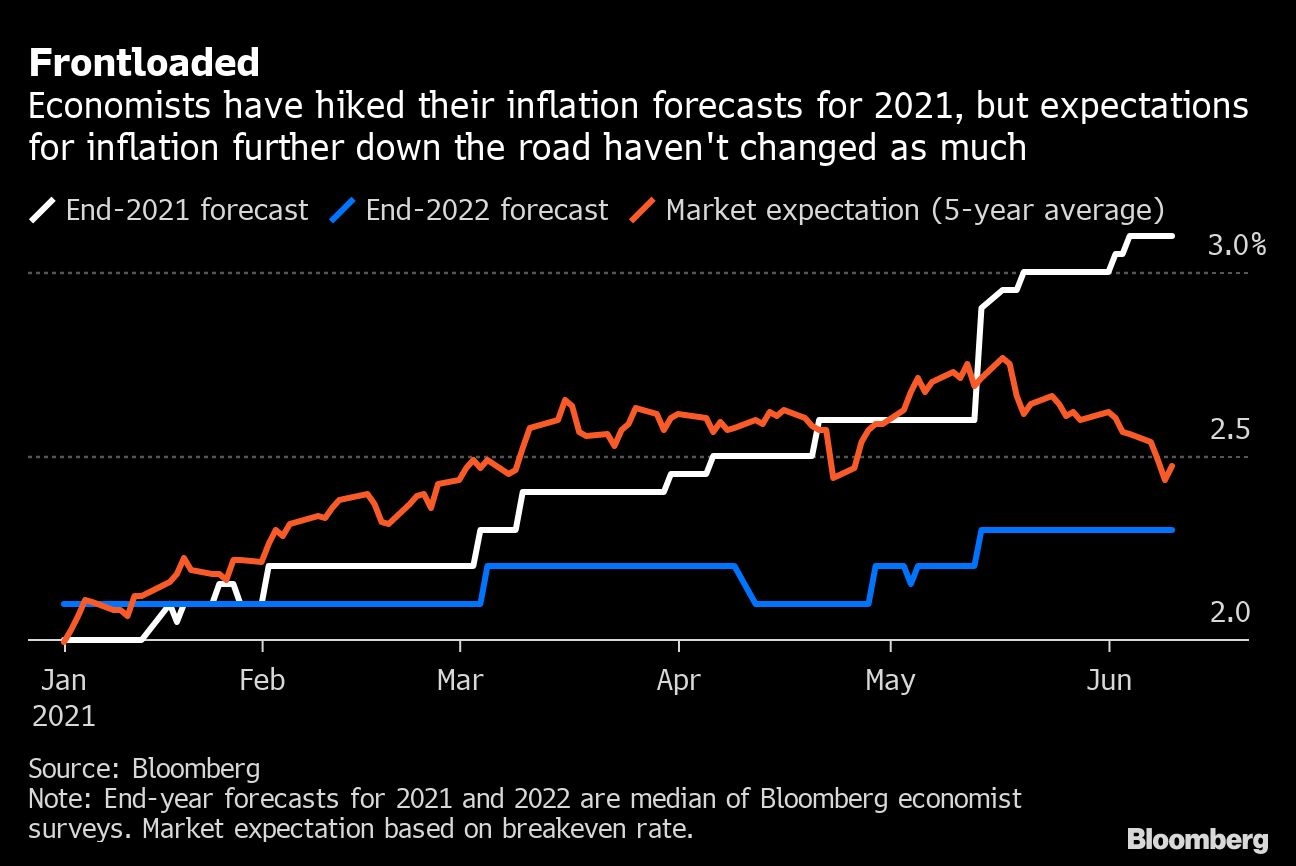

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell and his colleagues appear to be winning over investors with the argument that the current surge in consumer prices won’t last.

When news broke that U.S. inflation climbed to 5 per cent in May for the first time since 2008, yields on the key 10-year Treasury note moved in the opposite direction -- falling to a three-month low of 1.43 per cent on Thursday, before rising back up a bit early Friday. And while bond-market gauges of expected inflation edged upward, they remained well short of this year’s high reached in May.

That sanguine reaction is probably welcome news for Fed officials ahead of a June 15-16 interest-rate meeting – and it was bolstered Friday when a closely watched household survey showed that consumer expectations of inflation are declining too.

“Inflationary psychology takes some time to develop,” said Richard Curtin, director of the University of Michigan survey. “It’s not an instant response among consumers.”

The Fed is widely expected to stick with an ultra-easy monetary stance next week, in pursuit of the twin goals of maximum employment and 2 per cent average inflation. And they’ve been playing down risks that their policy could lead to a big and lasting overshoot on prices.

U.S. central bankers have been hammering home the message that higher inflation will mostly be transitory, the result of temporary bottlenecks as the economy reopens and low readings a year ago when it shut down.

‘Getting comfortable’

“The best thing the Fed has done, the most effective, is that they stayed consistent around the transitory narrative,” said Peter Yi, director of short-duration fixed income and head of credit research at Northern Trust Asset Management, which oversees roughly US$1 trillion.

Buttressing the Fed’s view, price increases in May were largely driven by categories where supply or demand has been skewed by the economy’s reopening, from used vehicles and household furnishings to airfares and apparel.

“A lot of the components that rose were the transitory ones,” said Yi. “More people in the market are now getting comfortable looking past these things.”

In a report to clients after the May data came out, JPMorgan Chase & Co. economist Daniel Silver agreed that the drivers of higher inflation are still mostly temporary -- but added that “there is some firming taking place away from these factors as well,” pointing in particular to increases in rents.

Billionaire investor Stan Druckenmiller said the Fed’s easy-money measures have lulled investors into a false sense of security and distorted asset prices. “The market is not speaking right now,” Druckenmiller told CNBC television in an email Thursday.

In discussing the outlook for inflation, Fed officials have stressed the importance of expectations: If people believe that prices are headed sharply higher, they act in ways that help bring that about. So the absence of financial-market fears of a big run-up in prices is undoubtedly comforting.

But only up to a point. Policy makers –- perhaps especially Vice Chairman Richard Clarida -- are well aware that the bond market does not give a completely clear reading of expectations, even among investors. It can be muddied by trader positioning, liquidity and other issues.

Flood of Cash

Indeed, financial strategists say bond yields have declined in recent days partly because of short-covering by investors who had previously bet on a move in the opposite direction.

The sheer flood of cash coming into the money markets -- a fact that’s been highlighted by unprecedented usage of the Fed’s reverse repurchase agreement facility -- is also a factor potentially supporting demand for Treasuries. Even at these levels, U.S. government debt offers more yield than many alternatives, including sovereign bonds in Japan and Europe.

Clarida, who served as global strategic adviser at Pacific Investment Management Co. before joining the Fed, is a self-declared “big fan” of a new index of common inflation expectations developed by central bank staff.

The index comprises 21 different measures of inflation expectations, including some drawn from the bond market, and is published quarterly. Clarida said last month that the index was in line with the Fed’s goal of an average inflation rate of 2 per cent.

Unlikely, not impossible

Randal Quarles, the Fed’s other vice chairman, has said that he puts more weight on consumer surveys of inflation expectations than on readings from the bond market.

“Ultimately what drives inflation is peoples’ expectations about what they’re going to need in the way of wages,” Quarles told a Brookings Institution webinar on May 26. “Those are imperfectly measured, obviously, but better measured by surveys rather than market-based measures.”

The latest University of Michigan survey of consumer inflation expectations, published Friday, brought encouraging news for Fed officials. Respondents said they expected inflation to average 4 per cent in the coming 12 months -- still high by the standards of recent decades, but down from 4.6 per cent a month earlier. Predictions for inflation in subsequent years also declined.

So far it seems unlikely that an inflationary psychology will develop, Curtin said. “But we can’t dismiss that issue out of hand.”