Oct 6, 2022

Inside CVC, the Secretive Buyout Firm Heading Into New Waters

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- In years past, CVC Capital Partners has hosted gatherings for senior employees in sun-kissed destinations like South Africa, Turkey or the French Riviera. The events typically kick off with morning meetings before shifting into team-building mode that includes activities ranging from mountain biking to paddle boarding.

It’s also where the firm has doled out its “Shark of the Year” award, a prize presented to the person who reeled in the most compelling deal for the private equity giant.

For a firm renowned for its hard-charging culture and pursuit of returns, the symbolism could hardly be more revealing. Over the course of several decades, CVC has perfected the art of the hunt, rising from a handful of professionals into one of Europe’s largest private equity houses, with 133 billion euros ($131 billion) in investments under management and 700 employees across 25 offices.

And despite owning stakes in high-profile assets ranging from Swiss watchmaker Breitling AG to the Six Nations Rugby competition, just how CVC goes about its business has remained largely beneath the surface.

Little is known about the company or its employees beyond a few public glimpses that paint a picture of an assertive culture. Rob Lucas, slated to become chief executive officer, documents his ascents to some of the world’s highest peaks, including Mount Everest in 2016, on social media. A bare-chested Alexander Dibelius, CVC’s head of Germany, is on Instagram bench-pressing his wife.

In 2016, the male-dominated firm attracted attention when it was the subject of a high-profile lawsuit filed by a female employee who alleged she was a victim of sexism. The suit was settled with no admission of wrongdoing on CVC’s part.

After much internal wrangling, CVC is now planning to shake off its secretive image and go public in Amsterdam or London at a possible valuation of more than $20 billion, in a move senior executives hope will seal its long-term future, according to people familiar with the plans.

CVC declined to comment on its plans for an IPO.

A public listing would mimic rivals like Blackstone Inc. and EQT AB and make it easier for CVC to finance deals and new investment strategies from the company balance sheet. Real estate and infrastructure are two areas the firm has identified where it wants to expand, some of the people said.

But an IPO will also move CVC into the public limelight, drawing examination of its operations, human-resources practices, as well as its compensation model. That’s a potentially risky embrace of transparency for a company and its founders, who have kept a remarkably low profile over the past 30 years.

No Rush

“Being public gives a private equity firm a different set of objectives,” said Geoffrey Geiger, head of private markets at Universities Superannuation Scheme, a £90.8 billion ($103 billion) pension manager that has invested in every CVC flagship fund since 2008. “If the investment committee’s attention is distracted by the need for fee-related earnings and lots of new products, then that might hurt the fund performance model.”

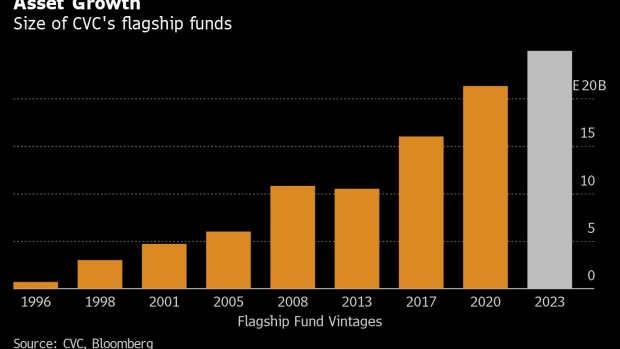

For the time being, CVC is in no rush to push a listing, preferring to wait for market sentiment to improve rather than risking its stock tanking on debut. The priority for now is to raise about 25 billion euros for its latest flagship fund, in what would be the firm’s largest pool of private equity money at a time when investors are increasingly nervous.

This story, a rare account of CVC’s way of doing business, is based on interviews with more than a dozen people, who asked to remain anonymous discussing the business practices of CVC.

The IPO considerations cap a three-decade rise since CVC was spun out of Citigroup Inc in 1993 by co-founders including Rolly Van Rappard, 62, Donald Mackenzie, 65, and soon-to-depart Steve Koltes, 66, each of whom have amassed fortunes since they struck out on their own in their 30s. Today, CVC pulls in more than 1 billion euros in annual revenue -- up from less than 250 million euros about 15 years ago, according to people familiar with the matter.

Close Knit

The close-knit relationship of the long-term employees means that CVC has traditionally elevated people from within. Many of the managing partners have worked at CVC for more than a decade, including Lucas, who joined in 1996.

Whenever CVC does bring in seasoned dealmakers, the firm taps experts in their respective fields, like Dibelius, arguably Germany’s best-connected banker as the former head of Goldman Sachs Group Inc. in the country. Then there’s Cathrin Petty, a rainmaker who joined from JPMorgan Chase & Co. in 2016 and helped build CVC’s healthcare-investment business.

Rather than operating under a centralized structure, CVC sources investment opportunities from dealmakers who operate independently in their local markets, resulting in a larger haul of ideas that are brutally winnowed down by the investment committee.

Once a week, the 11-member group for Europe and the US comes together to hear a string of intense pitches. To pass muster, a deal needs 80% approval from the room and is often scrutinized at least four separate times before approval, people familiar with the matter said. As one participant put it, you go into the meeting with no friends and you come out with even fewer.

Screening Process

The screening process helps explain why CVC’s loss ratio has remained below 1%. Over the past year, CVC signed non-disclosure agreements with about 400 targets, meaning they came into sight for investment. Actual deals boiled down to 19.

Where CVC sets itself apart is in the field of compensation for its dealmakers, something that will come under scrutiny if the firm goes public. Performance fees known as carried interest are the most lucrative part of working in private equity and the reason the industry mints so many millionaires.

At CVC, deal teams pocket the bulk of any spoils that come from the transactions they handled. The approach has long been credited for attracting and retaining top talent who can earn millions early in their career if they land on successful deal teams.

The distribution model means even those sitting at the very top are kept hungry because they cannot be expected to passively rake in big profits from deals in which they weren’t involved.

How the carry is carved up has to be approved by three senior executives. Sometimes, a junior employee can earn more than a managing partner if they played a bigger role in landing a deal.

That gives CVC a more meritocratic tinge. But the same approach is true of losses. Those who bring in duds need to recoup lost compensation for the firm before they can share in future spoils.

Speedy Decisions

Executives that have run companies under the CVC umbrella say the firm’s speed of decision-making and expertise have been important ingredients to grow the businesses. A case in point is the firm’s 2017 acquisition of Breitling. CVC bought a majority stake and recruited industry veteran Georges Kern from luxury emporium Richemont SA to head the business. Kern overhauled marketing, focused on bestselling models and redesigned the retail network.

By late 2021, CVC sold a minority stake on to Partners Group Holding AG, an investment that valued Breitling at about 3 billion Swiss francs ($3 billion). That’s more than three times the value at the time of CVC’s initial involvement.

The single deal that cemented CVC’s reputation with investors, and helped it emerge from the financial crisis with its return performance unblemished, was the purchase of the Formula One car-racing business in 2006.

The deal’s performance ensured that a fund packed with otherwise unremarkable companies stood out as rival managers struggled to stay above water during the turmoil of the financial crisis.

By the time CVC sold the business to Liberty Media Corp just over a decade later, the buyout firm returned 500% to investors, ranking among the best returns on record and marking a pivotal moment for CVC as it built out its brand globally.

As the firm’s buyout business delivered stellar returns, CVC followed in the footsteps of larger US peers by launching new strategies. These included a fund which can hold onto assets for longer, as well as an arm which buys fast-growing technology companies.

Growth Areas

Last year, CVC bought secondaries business Glendower Capital. The acquisition was financed in part by CVC’s sale of a stake in itself, in a deal valuing the business at $15 billion, according to a person familiar with the matter.

Not all deals have been spun into gold. Some, including Autobar or Australian media company Nine Entertainment, saw CVC’s investment wiped out. The firm’s $290m investment in Chinese restaurant chain South Beauty led to litigation as CVC sought to recover money from the founder by seizing a Warhol painting and several New York apartments.

Besides the investment misses, CVC faced what one former employee described as a moment of reckoning when former managing director Lisa Lee filed a lawsuit against the firm that was made public in 2016. Following the settlement, CVC said in a statement that “the private equity industry benefits from the diversity of its talent and that continuing to recruit and develop a diverse pool is an important goal.”

Diversity Issues

At the time, fewer than 10% of all dealmakers at CVC were women. Several former staff said the firm had an aggressive macho culture, a by-product of its winner-takes-all approach. The company only set up a human resources committee in 2009, 16 years after it was spun out of Citigroup.

Following Lee’s lawsuit, CVC put in place a goal to boost the percentage of female dealmakers at the firm to 20% by 2020. After hitting the target, the firm now has a plan to ensure a quarter of its investment professionals are women by 2025.

CVC’s investors are typically public pension funds, sovereign wealth funds and wealthy individuals. In recent years, pension funds in particular have begun taking a harder look at the ethics of the firms where they place their money.

In a bid to move away from its shark-tank image, CVC appointed Merary Soto-Saunders as its first head of diversity and inclusion earlier this year. Despite improvements in the junior ranks, she has still work to do: at this point, Cathrin Petty is the only woman among the ranks of 34 managing partners.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.