Nov 18, 2021

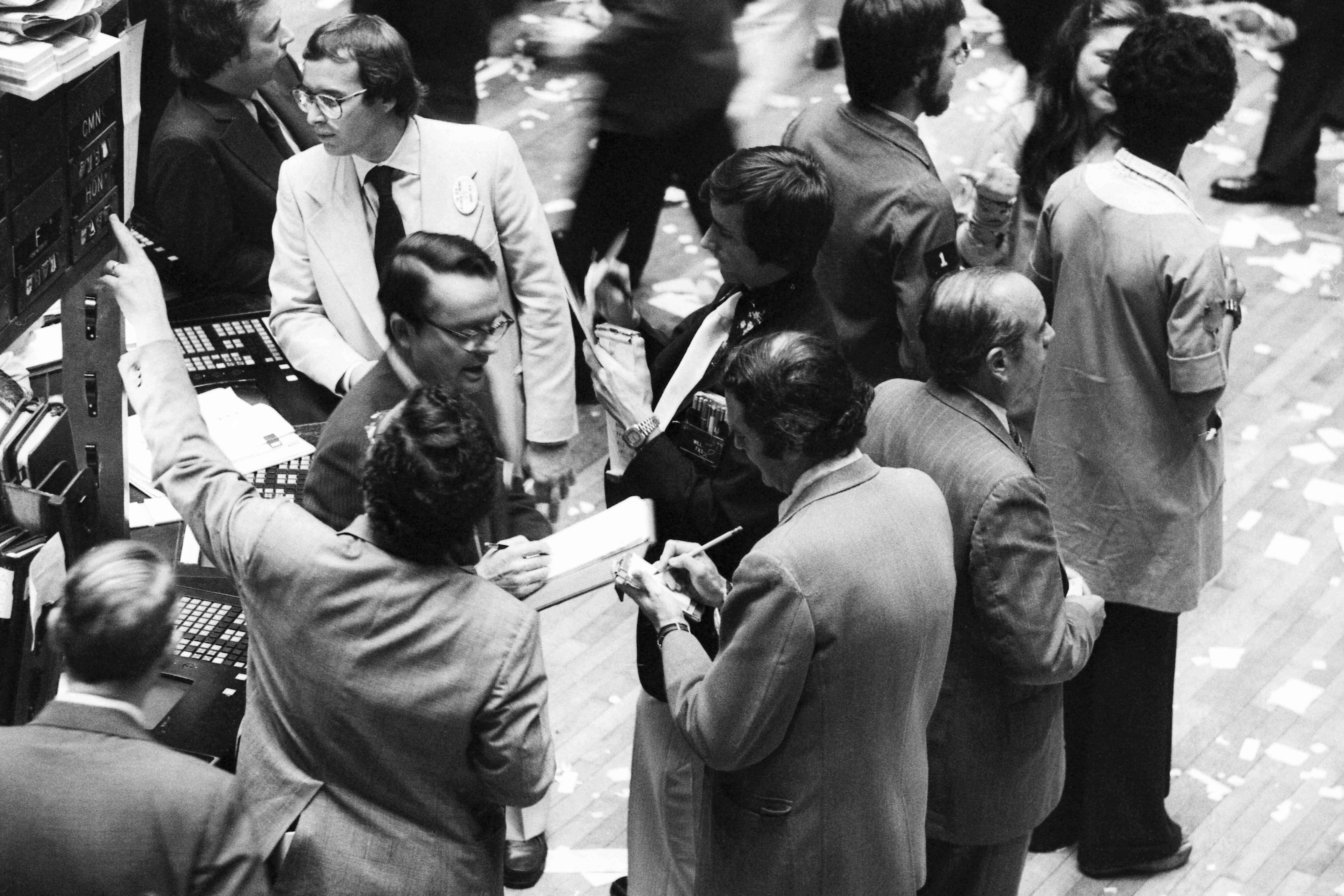

Getting inflation right is a make-or-break moment on Wall Street

, Bloomberg News

The Fed should raise rates in 2022 akin to the BoC to prevent overheating the U.S. labour market: Chief economist

God help whoever on Wall Street botches the inflation call.

After a three-decade hiatus, anxiety about rising consumer prices is testing the analytical skills of money managers and professional traders like nothing since the short-lived pandemic panic. The stakes couldn’t be higher: The long regime of mild inflation and low interest rates has helped to drive up stock and bond valuations. Now, with inflation unexpectedly hitting 6.2 per cent in October from a year earlier, something new is on the horizon. A daisy chain of supply bottlenecks has driven prices higher as companies fight to guard their profits and consumer demand remains high. Is it a post-pandemic blip that will resolve itself? Or a sign of more turbulence to come?

For people working in finance, it’s a moment of extreme career risk—or a chance to be a hero to their bosses and their clients if they get it right. Many have never been here before. “There’s people that are halfway, a third of the way through a career and they haven’t seen inflation,” says Kim Forrest, founder and chief investment officer at Bokeh Capital Partners.

Inflation is the first hurdle every investor has to clear, and it’s baked into every pro’s model of the fair price to pay for a bond or a stock. But it’s not easy to get a read on how investors are processing the latest spike. Wall Street strategists are flummoxed. Of the 21 forecasters tracked by Bloomberg, the lowest yearend target for the S&P 500 index is 3800 and the highest is 4800—that 26 per cent spread is among the widest in a decade.

In the Treasury market, volatility is surging. And a recent note from Goldman Sachs observed that the companies most beloved by hedge fund long traders are also the stocks most beloved by hedge fund short sellers—the ones who bet on stocks falling. In other words, professional speculators evidently expect the same stocks to rally and to plunge.

Everyone has a different take, but everyone is increasingly focused on the same consumer price index releases. “There’s so much concern because we haven’t seen this kind of inflation in many, many years,” says Kathy Jones, Charles Schwab Corp.’s chief fixed income strategist. “The thought really was that it was going to come down very quickly, and it hasn’t come down as quickly as expected, because we seem to roll from one supply-demand imbalance to another.”

Still, the S&P 500 is up about 25 per cent in 2021. In the long run, stocks are almost always a buffer against inflation: Good companies get to raise their prices—and profits—even as their costs go up. A year ago, some bulls liked to talk about the “reflation” trade, or a happy combination of booming growth and increased pricing power for companies.

For long-term buy-and-hold investors—including individuals investing their own money—this may make getting inflation “right” a less fraught problem. Thinking ahead for the next two or three years, “I’m looking for the very best companies,” says Forrest. “Inflation or not, that equation hasn’t changed.” Inflation is more of a threat, she says, for investors facing shorter time horizons: “If I’m looking a year out, I’m kind of screwed. I have to get it right.”

One risk for stocks is if inflation is so surprising and disruptive that it forces a sudden change in interest rates and market psychology—and causes investors to reassess their portfolios. “It wouldn’t be a 5 per cent to 10 per cent correction and then we bounce back,” says Michael Shaoul, chief executive officer at Marketfield Asset Management. “There’d be significant losers.” The danger, to Shaoul, is that bond investors reach a “psychological breaking point” on the low yields they’ve been collecting. Already, the real annual yield on a safe 10-year Treasury—accounting for the market’s expected inflation—is a percentage point below zero. For the moment, investors seem to care as much about having a haven as they do about staying ahead of inflation.

But what if that changed? To avoid losing even more money to inflation, fixed-income money managers might start demanding higher yields, which would mean forcing down bond prices. Pain in the bond markets could roil equities in a fashion similar to the late 1960s to early 1980s, Shaoul says. In a high-interest-rate environment, investors could reevaluate the prices they’ve been willing to pay for equities, bringing down price-earnings ratios even if profits remain solid.

What happens next may hinge on the Federal Reserve. The central bank begins reducing its bond-buying program this month and may end it by mid-2022, and markets expect that a handful of interest rate increases will follow. It’s too soon to tell if inflation will speed up that timeline, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco President Mary Daly said on Nov. 10.

Matt King, global markets strategist at Citigroup Inc., says the central bank may need to move faster. Although raising rates won’t necessarily “improve the availability of truck drivers,” he said recently on Bloomberg’s Odd Lots podcast, it could tamp down demand. But a quicker rate move would also slow down growth—and be painful for investors who’ve gotten used to the Fed propping up asset prices, he said.

Marketfield’s Shaoul suggests that the risk is more that investors just start seeing the world differently—as a place with inflation in it—and that it’s hard to predict a shift like that. “Emotional changes take a long time and are always unlikely to happen, but if they do happen the world can move really fast,” he says. “Once the light switches, it’s very hard to put it back.”

SEARCHING FOR SHELTER

Rising prices have investors looking for ways to protect their purchasing power. Some ideas might be better than others. —Vildana Hajric

BEST BETS

Series I U.S. savings bonds

Their rates are periodically adjusted for inflation, and right now they pay over 7 per cent.

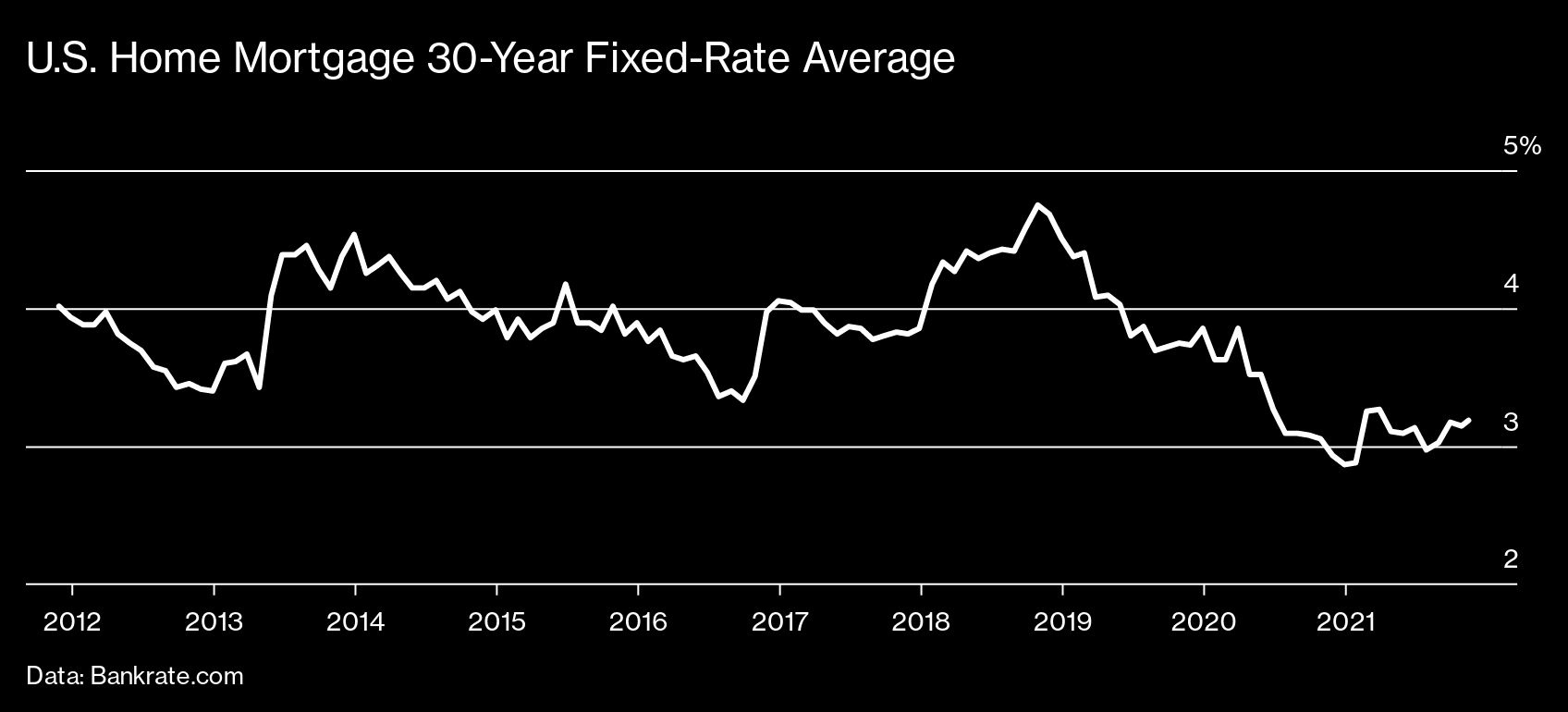

A fixed-rate mortgage

Rates are still very low at just over 3 per cent, and if you lock them in now, you don’t have to worry about your housing costs rising.

Stocks

As long as inflation isn’t too hot for too long, many companies have pricing power to pass on costs to consumers, says Keith Lerner, co-chief investment officer at Truist Advisory Services.

WORTH CONSIDERING

Inflation-hedged ETFs

Every single exchange-traded fund with inflation in its name has had inflows this year. Some focus on stocks in industries that do well when prices rise, such as energy and materials.

Real estate investment trusts

Not in the market for a house right now? REITs are an easy way to get diversified exposure to housing prices. But the market could cool if rates go up.

TIPS funds

These buy special Treasury bonds that have their principal value adjusted for inflation. The downside: If inflation calms down, you might make more money in regular Treasuries, says fixed-income strategist Karissa McDonough at Community Bank Trust Services.

ROLL THE DICE

Gold and crypto

Fans of each consider them hedges against currency devaluation. But Cam Harvey, a professor of finance at Duke, says both are also prone to speculative manias and crashes. The timing of when you buy could matter a lot more than what happens to consumer prices.

Collectibles

Rare wine. Vintage cars. Art. They may be fun to own but are hard for amateurs to value, difficult to quickly sell, and expensive to store. “They’re more often just a product being sold by any means necessary instead of a genuine inflation hedge,” says George Pearkes at Bespoke Investment Group.