Jul 9, 2021

Fund managers have much to fear from inflation

, Bloomberg News

Equity returns likely to be more compressed: BlackRock's Kurt Reiman

Central bankers might sound relaxed, but inflationary pressures are quickly rising, and not just in the U.S. For example, more manufacturers say they are paying higher prices for materials than any time since 1979, according to the Institute for Supply Management’s report for June. If that wasn’t problem enough, central bankers are still too focused on preventing deflation, which means that whenever they act it will surely be too little and too late.

Put it together and inflationary outcomes are likely to be consistently higher in coming months and years. Not only does that spell trouble for the fund-management industry in general, it is likely to be especially problematic for the biggest firms and thus bring an end to the rapid consolidation in the industry.

Driven by extraordinarily easy monetary policies of central banks, the performance of financial markets has been historic. The S&P 500 Index has returned about 230 per cent since June 2011. You also would have had a hard time not doubling your money in corporate bonds. No wonder cash has flooded into the fund management industry. The amount invested in regulated funds globally grew to US$63 trillion last year from US$28 trillion in 2011, according to the Investment Company Institute. (Some of the increase was, of course, down to performance.)

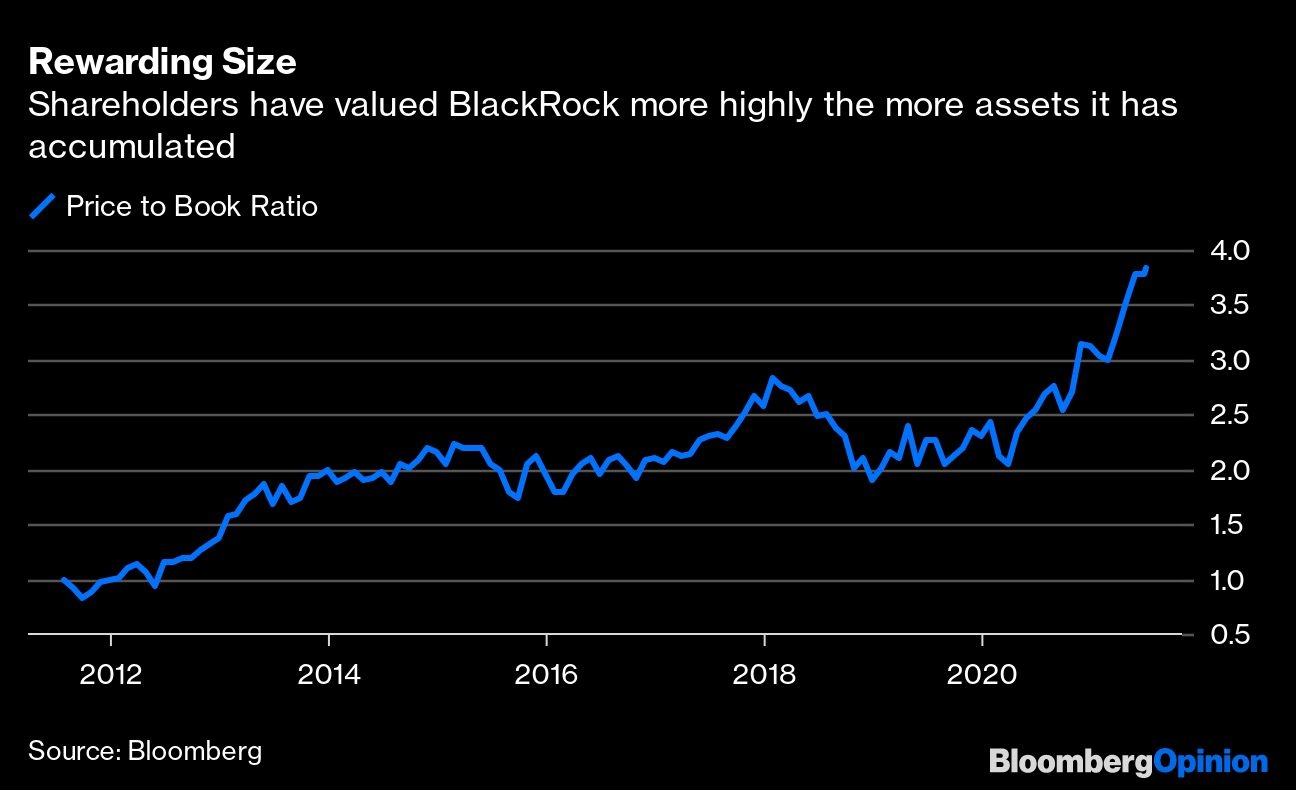

Nevertheless, fund managers have faced pressure to bulk up, mainly because of the constant downward pressure on fees. But increased regulatory burdens and spending on new technology, among other things, have pushed costs higher. Hence the need for scale. Echelon Partners reports that there were a record number of deals in the asset-management business last year. The stock market has rewarded size. BlackRock Inc., which now accounts for about 40 per cent of the S&P 500 Asset Management & Custody Banks Index, has a share price that has doubled to 3.8 times its book value since the end of 2018.

The snag is that, from a long-term perspective, being big brings other problems. Foremost among these is the thing that fund-management firms are selling: returns. Although executives and shareholders are clearly betting that financial markets will continue to attract investors, this is nonsense. Consider that huge ex post returns (what you’ve had) have driven long-term ex ante returns (what you can expect) to almost nothing at best in many asset classes. In some cases, ex ante long-term returns are negative.

The U.S. is perhaps the most extreme – and certainly the biggest – example. Of all the available valuation metrics for stocks over the longer term, the ones that provide the best guide to future returns use some variant of cyclically adjusted earnings. In short, the higher the multiple of earnings you pay now, the lower the subsequent returns. The chart below looks at 10-year estimated returns compared with actual outcomes. It is a very decent fit. We are very near the top of the valuation range for the past 100 years. As a result, ex ante returns are about 3 per cent before inflation takes its cut. That means in real terms, current returns are negative.

![]()

Government bonds look worse. Yields on 10-year U.S. Treasury notes are about minus 0.80 percentage point after taking into account inflation. This means that if the market’s inflation expectations are correct -- admittedly a big if -- investors will lose an inflation-adjusted 80 basis points every year for the next 10 years.

Corporate bonds look pretty awful no matter what part of the market you consider. The lower the credit quality, the more like equities they behave; the higher the credit quality, the more their performance mirrors Treasuries. Given the valuation of equities, it perhaps shouldn’t be a surprise that yields on sub investment-grade bonds — junk to you and me -- have never been lower either in absolute terms or relative to Treasuries. At some point, credit investors are likely to be clobbered by falling equity prices or rising Treasury yields — or, as is the way with credit, both.

Never before have all broad asset classes been so expensive at the same time. This leads to at least two problems for asset-management firms, especially the biggest ones. The first is that they are very unlikely to protect investors even in funds that are discretionary: business and career risk mean that, although they might trim weightings at the margin, they almost never do anything radical to their holdings or even anything that would actually help much. Second, and more importantly, the consolidation in the industry means a few behemoths control an outsized percentage of assets. They are the market. Blackrock alone manages US$9 trillion. Smaller, discretionary funds can at least be nimble and quickly take measures that protect their investors.

Which brings us neatly back to inflation. Central banks can only continue to drive up asset prices if inflationary pressures remain muted. Most in the fund-management industry, you may not be surprised to hear, agree with central bankers. In a recent survey by Bank of America Corp., almost 75 per cent of respondents said they expect recent inflationary pressures to be short-lived. They might be right, but if they are wrong and inflation rates keep creeping higher over time, I can’t help but think that at some point financial assets will have a nasty reaction given their lofty valuations. The skew of returns 36 months from when you invest is very pronounced to the downside when valuations are the richest.

Ironically, the best that fund-management firms could hope for is a crash in financial-asset prices, thus resetting valuations lower. They would probably blame the plunge on unforeseen circumstances, which is what generally happens. But the truth is that the prices of pretty much every financial asset have been pumped higher by central banks — and they should know this.