Mar 15, 2023

Crisis Narrative Forcing Out All Others in Bank-Obsessed Markets

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Is upheaval in the banking sector the prelude to a financial crisis, or just the biggest bump yet on the road to restoring order to the economy? Stock investors clinging to hopes this too shall pass are having their tolerance for pain severely tested.

Snowballing tensions over the banking sector, now gone global after Credit Suisse saw a quarter of its market value lopped off over five hours, torpedoed a nascent rally in equities Wednesday, as systemic risk in the financial system started to blot out the impulse to buy. While US equities pared back the worst of their losses, they still finished lower as warnings of contagion swirled.

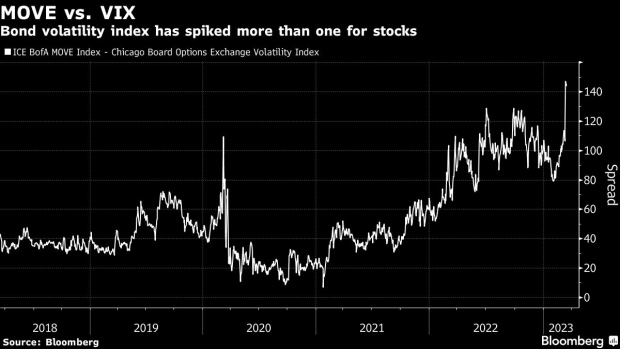

Battling narratives over how pervasive a risk bank stress poses to the economy had opened one of the widest gulfs ever between equity and Treasury volatility in the aftermath of three bank failures in the past week. The gap began to shut on Wednesday as fear of everything from a recession to cascading bank runs sent stock investors fleeing.

“If there’s a lack of confidence in the bank sector, which is the lifeblood of the US and every economy, that’s an event risk that equity markets need to react to,” said Anastasia Amoroso, chief investment strategist at iCapital.

The crisis at Credit Suisse, catalyzed by comments from its largest shareholder that it wasn’t open to further cash injections into the beleaguered bank, sparked a rush for havens. Financials in the US were among the hardest-hit, with the sector dropping 2.9%, while energy shares lost 5.4%.

Up-and-down moves in the S&P 500 suggest equity investors have been less willing than their fixed-income counterparts to jettison the bull case. That case is, in condensed form, that government backstops would stanch the impact of failures at lenders whose role in the economy was limited to begin with, while still-flush consumers keep spending.

Moves in the Cboe Volatility Index illustrate the resistance among stock traders toward worst-case outcomes. While the so-called fear index has perked up in the last few days as contagion worries spread, the VIX remains well below levels hit multiple times in last year’s bear-market plunge. Hopefulness is also evident in various money flow measures. A net $1.11 billion flowed into the SPDR S&P Regional Banking ETF (ticker KRE) on Tuesday.

Bond traders have seen it differently. While internal forces were at play in that market, most notably a short squeeze among speculators who foresaw a continuation of Federal Reserve rate hikes, the plunge in yields that occurred between Thursday and Monday was read as an emphatic bet that the collapse of SVB and others would gravely wound the economy — enough that the war against inflation would become an afterthought.

Investors in fixed income rushed into the safest corners of the market again Wednesday, with Treasuries surging across the curve and the 10-year yield plummeting more than 20 basis points to 3.46%. The yield on the two-year fell more than 30 basis points to around 3.9%.

“Idiosyncratic risks are certainly bubbling to the surface in areas that were weak to start,” Emily Roland, the co-chief investment strategist of John Hancock Investment Management, told Bloomberg Television. “This is the way that every economic cycle ends, unfortunately — the Fed tightens until something breaks, and there’s going to be a confidence issue when the Fed here pushes you to the edge of a cliff.”

Some worst-case fears eased Wednesday afternoon following news that Swiss authorities and Credit Suisse are discussing ways to stabilize the bank, according to people familiar with the matter, boosting the tech-heavy Nasdaq 100 into positive territory. Even still, the hit to confidence has stoked fears that lenders will be more focused on shoring up their balance sheets than on providing loans — threatening a lending crunch that could tip the economy into recession.

A team led by Michael Schumacher, a macro strategist at Wells Fargo, looked at how markets behaved before and after SVB collapsed and found some similarities with the days surrounding Lehman Brothers’ failure in September 2008. Among them were a nearly identical plunge in two-year Treasury yields in the days before the event, a weakening dollar and a roughly comparable selloff in the S&P 500.

“Our overall view is that economic and financial fundamentals are much stronger today than in 2008,” they wrote. “However, in several ways markets seem even more disjointed now than they were 15 years ago.”

That surge in bond volatility was dramatic enough that trading was briefly halted in a key corner of the US rates market Wednesday. The two-minute pause halted trading in June, July and August futures linked to the Secured Overnight Financing Rate, as well as Fed Funds futures for August and September — a relatively rare event.

While a full-blown credit crisis still may be a long shot, the events of the last week are likely to have lasting consequences for the banking sector, and may be enough to tip the scales toward a recession. Lenders struggling to retain deposits will see funding costs rise, potentially curbing the flow of credit to the economy. That would seem to be the scenario being priced in by bonds, which have largely discounted odds the Federal Reserve will have any need to push rates higher to fight inflation.

“It’s definitely a psychological issue — that’s what it comes down to,” Bloomberg Intelligence’s Michael Casper said in a phone call. “And the impact to the market is very much the same — if worry ensues, it’s going to cause a hit to stocks.”

--With assistance from Lu Wang.

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.