Jan 25, 2023

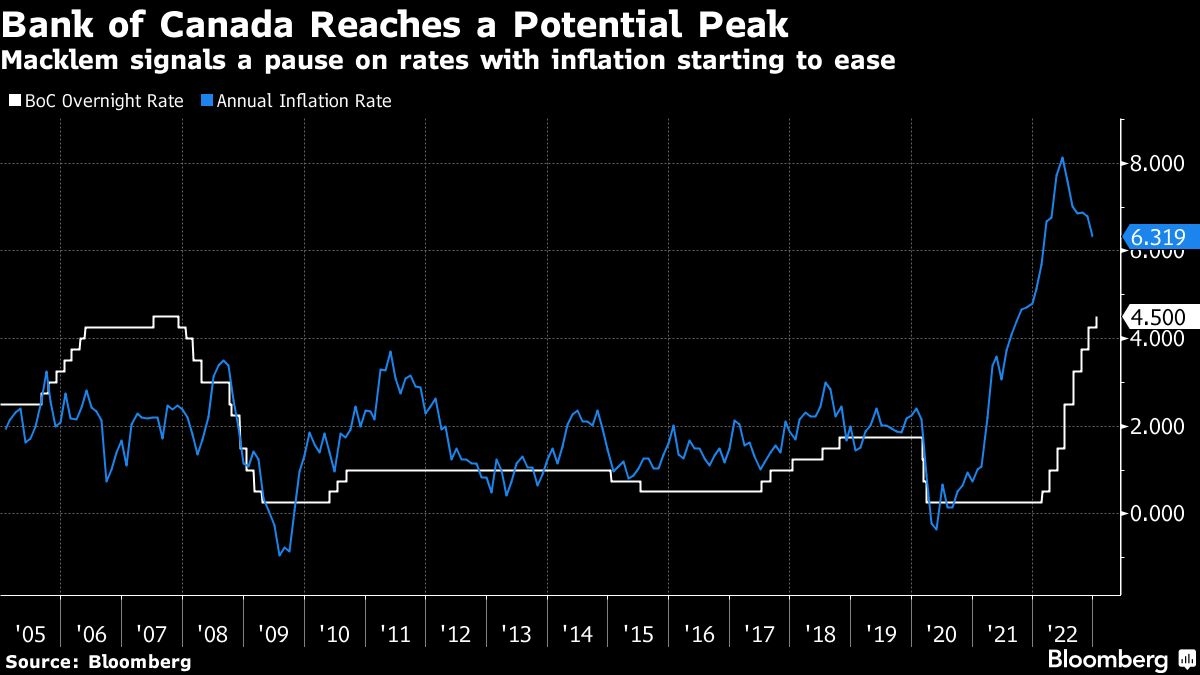

Bank of Canada raises interest rates to 4.5% and plans to hold

, Bloomberg News

It's the right decision for the Bank of Canada to hike by 25bps today: Andrew McCreath

The Bank of Canada raised interest rates for an eighth consecutive and potentially final time, saying it expects to move to the sidelines and assess the impact of its rapid tightening on the economy.

Policymakers led by Governor Tiff Macklem increased the benchmark overnight lending rate by 25 basis points to 4.5 per cent on Wednesday, the highest level in 15 years. Bonds rallied and the loonie dropped sharply.

While the quarter-percentage-point hike matched expectations of markets and economists, most analysts didn’t see the central bank explicitly declaring a potential end point to rate increases.

Canadian government bond yields and the currency fell as investors digested the central bank’s indication it will hold rates steady.

The loonie dropped as low as $1.3428 per U.S. dollar after the decision, before paring those losses. The yield on Canada two-year bonds dropped to 3.57 per cent at 2:09 p.m. Ottawa time, down about 8 basis points on the day. Two-year U.S. Treasury yields briefly dipped a couple of basis points after the news.

Inflation is now forecast to slow to three per cent by midyear and return to the two per cent target in 2024. Officials said falling three-month core measures of inflation may be a signal that underlying price pressures have peaked.

In the quarterly monetary policy report published alongside the decision, officials said the economy is still overheating. But growth is expected to decelerate rapidly. Higher rates are weighing on the real estate market and on household spending, likely helping to cool growth and inflation.

“If economic developments evolve broadly in line with the MPR outlook, Governing Council expects to hold the policy rate at its current level,” the bank said in the rate statement.

Still, policymakers cautioned that more hikes may be needed if economic data surprise to the upside. The bank “is prepared to increase the policy rate further if needed to return inflation to the two per cent target.”

Swaps trading suggests markets expect the bank’s next move to be a rate cut, potentially as early as October.

Asked about the possibility of a rate decrease this year during a press conference, Macklem said it’s still “far too early to be talking about cuts.”

Carolyn Rogers, the bank’s senior deputy governor, said the bank would need to see “accumulated evidence” that economic momentum and price pressures have turned for policymakers before boosting rates again.

The conditional pause — the first among Group of Seven central banks — suggests officials are convinced the current policy rate is restrictive enough to restore price stability.

BALANCING RISKS

In his opening statement at the press conference, Macklem acknowledged that the full impact of his hikes so far “is still to come,” given their speed and magnitude. The overnight rate has gone from 0.25 per cent to 4.5 per cent in less than a year.

“We are trying to balance the risks of under- and over-tightening,” Macklem said. “If we do too little, the decline in inflation will stall before we get back to target. But if we do too much, we will make the adjustment unnecessarily painful and undershoot the inflation target.”

The Bank of Canada “provided some unexpected guidance that this may be the peak” for rates, Andrew Grantham, an economist at Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, said in a report to investors. He predicted that this will be the last increase.

In their report, officials raised their estimate of economic growth in 2022 to 3.6 per cent and forecast a 1 per cent expansion this year, up from 3.3 per cent and 0.9 per cent in their October projections. They said the chances of two consecutive quarters of negative growth, a so-called technical recession, are “roughly the same” as a small expansion in 2023.

The Bank of Canada, which led its global peers in raising rates rapidly last year, could now be laying out a blueprint for how they pivot to pausing.

Globally, the economic outlook is improving because of Europe’s resilience during an energy crisis, China’s reopening, declining commodity prices and easing supply challenges.

In Canada, it’s a mixed picture. The labour market continued to add jobs at the end of last year. On the other hand, highly-indebted households are feeling the pinch of higher rates and rising costs for shelter and food. And there’s a risk that inflation in services will remain high, if businesses continue to have trouble finding the workers they need, officials said.

For the first time in its history, the Bank of Canada will give the public a glimpse of its rate-setting process, joining central banks such as the U.S. Federal Reserve and Bank of England in sharing records of their meetings. A minutes-like summary of the bank’s deliberations will be published on Feb. 8.