Jun 23, 2021

Amazon is cagey about the primeness of Prime Day

, Bloomberg News

Amazon announces support of U.S. bill to legalize pot

Amazon.com Inc. loves to pile on the superlatives when it sums up its annual Prime Day shopping event. This year was no different, with its press release trumpeting “biggest days ever,” “record-setting” activity and “incredible” results. But a careful parsing of the 2021 release, along with the peculiar circumstances surrounding this year’s event, could signal business may not be as buoyant as it seems.

To a casual observer, the e-commerce giant’s self-created, two-day holiday — which took place on Monday and Tuesday — would appear to have done quite well. On Wednesday, Amazon bragged how Prime members bought more than 600,000 backpacks, 1 million laptops and 40,000 calculators while listing other top-selling products such as Keurig K-Slim coffee makers and iRobot Roomba robot vacuums. That all sounds impressive, but cherry-picked details do not tell investors much about the strength of the overall business. For that, the press release left little to go on.

While Amazon did say this year’s Prime Day event was the biggest two-day sales period for its third-party sellers, it didn’t provide specific details as it has in years past, and that’s telling. Last year, for instance, Amazon gave concrete Prime Day numbers for third-party merchant sales of US$3.5 billion, which was up about 60 per cent compared with those in the prior year. There are usually reasons behind the decision to reveal or not reveal certain details. For all we know, sales may have grown only marginally, which would be a big disappointment. One can’t help thinking that Prime Day must have underwhelmed.

Anecdotally, there was considerably less buzz about the event among my friends and family. On Monday, Bloomberg News reported merchants were less aggressive this year in offering discounts amid supply chain disruptions, lower inventories and rising costs. An uninspiring performance would be a problem because there were high financial expectations from analysts and research firms. EMarketer had estimated U.S. Prime Day sales would generate US$7.3 billion of sales this year, an amount that would account for 6 per cent of Wall Street’s sales forecasts for Amazon’s June quarter and represent an increase from US$6.2 billion last year.

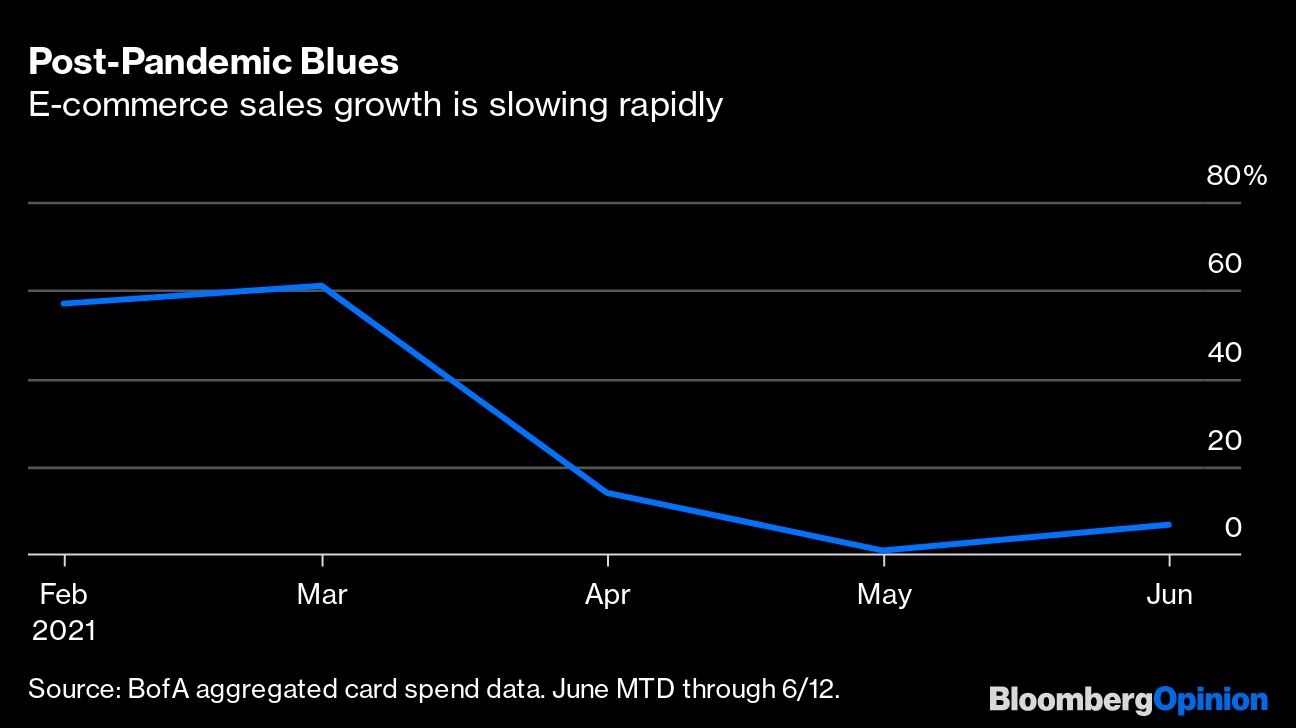

Amazon may be facing headwinds from a slowdown in the entire e-commerce category, which faces tough comparisons from the peak pandemic months last year. Bank of America credit-card data show a steep drop in e-commerce sales growth: After surging 61 per cent in March from a year earlier, online sales rose just 1 per cent last month, according to the bank. Indeed, this trend and the desire to prop up sales in the current quarter may have been part of the reason that Amazon decided to move Prime Day to June from its typical July time slot.

These crosscurrents come at an inopportune time for Amazon. The technology giant is attracting increasing regulatory scrutiny on anticompetitive grounds around the world. This week, a House committee is considering an array of antitrust legislation that, if passed, could force Amazon to disband its private-label product lines that compete with third-party sellers on its marketplace and ban preferential treatment for its own offerings. (It’s probably not a coincidence Amazon has been repeatedly marketing itself as a champion for small business in its news releases.) And, of course, Amazon faces uncertainty over its leadership for the first time in its history with Jeff Bezos stepping down as chief executive officer on July 5.

In the end, Amazon’s biggest challenge may be beyond its control. For much of the past year, many of us have been stuck at home and shopping online, loading up on gadgets and consumer goods. In a sense, we were pulling demand forward. But as the economy reopens, we will increasingly shift our spending toward dining, traveling and other outdoor activities. E-commerce sales may well remain lackluster for the rest of the year — so much so that Amazon may regret moving its Prime Day earlier.