Apr 19, 2024

Fed's uncertain path creates bind for Bank of Canada's Macklem

, Bloomberg News

Canada rate cuts expected before the U.S.: RBC's chief economist

The Bank of Canada is getting closer to cutting interest rates, but there are limits to how far and how fast it can move without getting a clearer sign from the U.S. Federal Reserve.

Governor Tiff Macklem said last week officials are mulling when to cut the bank’s benchmark overnight rate from five per cent, and he kept the door open to easing as early as June. With core inflation decelerating, markets are putting the odds of a cut at the next meeting at about two-thirds. A cut in July is fully priced.

In the U.S., the immediate path for easing rates appears less certain. Traders expect just one or two cuts from the Fed this year, a sharp change from the start of this year, when they were looking for five or six. Some Fed officials believe it’s possible there will be no cuts at all in 2024, given stronger-than-expected growth and sticky inflation.

That’s raising questions about how deeply the Bank of Canada can lower rates this year, and whether policymakers will eventually be forced to pause and wait out the Federal Reserve.

The larger the gap between the two countries’ policy interest rates, the greater the potential for downward pressure on the Canadian dollar. A weak loonie means higher import costs, risking higher inflation at a time when the central bank is still straining to get back to the two per cent target.

“Markets are coming to terms with the Fed staying on hold for longer than expected, while the Bank of Canada is still on course for mid-year rate cuts,” Andrew Kelvin, head of Canadian and global rates strategy at TD Securities, said by email. “It won’t limit the timing for Macklem’s first two or three rate cuts, but as we go further into the easing cycle, potential divergence from the Fed might be a limiting factor.”

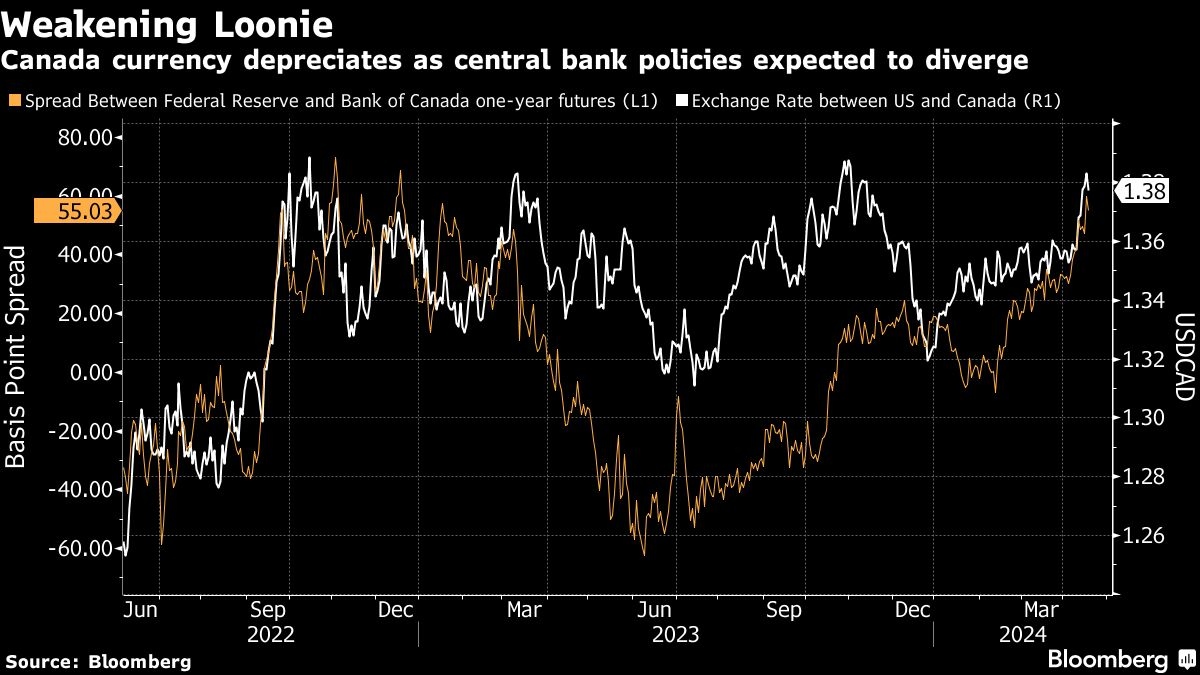

Canada’s currency has depreciated relative to the U.S. dollar as the outlook for the two economies shifts. At $1.377 per U.S. dollar, it’s already near the weakest level since November.

One-year swaps suggest policy rates in the U.S. will stay more than 50 basis points higher than Canada’s over the next year, a spread that’s widened substantially. Canada is seen having slower growth and quicker disinflation over that period.

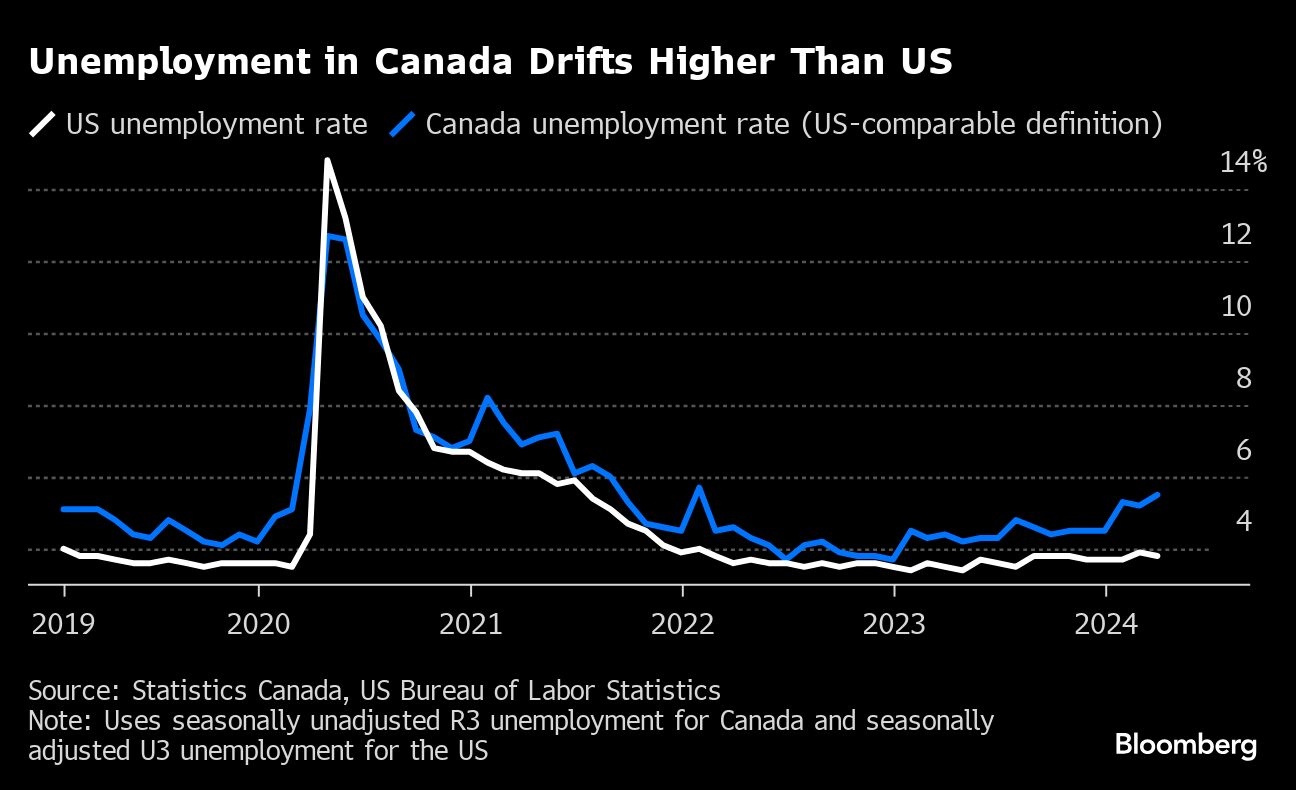

As with the Bank of England and the European Central Bank, it’s becoming clearer that the Bank of Canada’s monetary policy settings don’t need to stay as high for as long as they’re expected to in the US. Canada’s core inflation cooled again in March and the central bank says it’s increasingly seeing evidence that higher borrowing costs are working to slow the economy and create slack in the labour market.

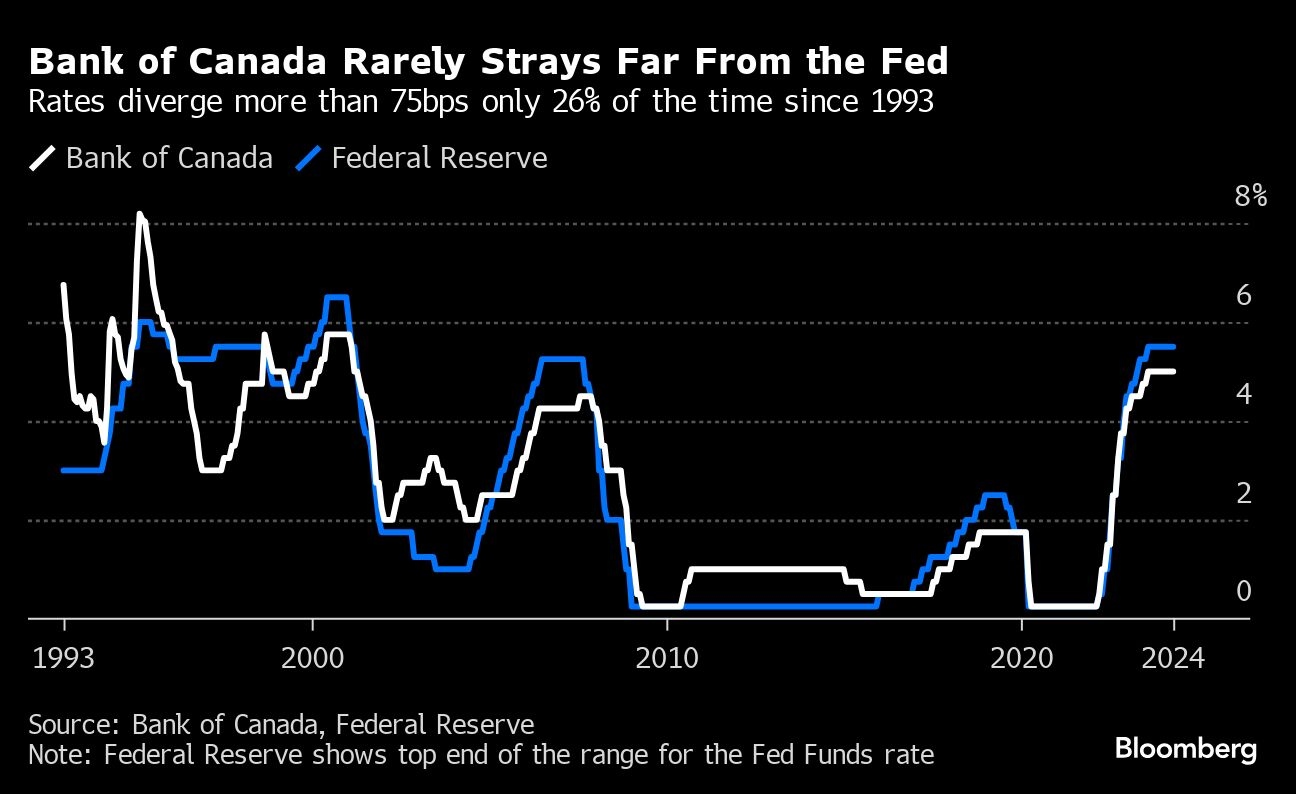

But economists surveyed by Bloomberg are split on how much the two country’s policy rates can comfortably diverge. In March, about 40 per cent said 100 basis points was the maximum spread before distortions occur. About 30 per cent think the limit is 50 basis points.

Historically, Canada’s rate path has tightly followed the Fed’s. The U.S. and Canada are major trading partners and their economies are deeply intertwined — periods of wide disparity in their economic performance are often short-lived.

“Anything more than three cuts begins to exert an uncomfortable pressure on the currency,” Ian Pollick, global head of FICC strategy at Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, said by email. “Using the Bank of Canada’s own models, we find the near-term limit of divergence to be around this level.”

According to Charles St-Arnaud, chief economist at Alberta Central, the typically strong correlation between the Canadian dollar and oil prices has been disconnected since 2022. Therefore, “if the loonie is less influenced by the level of oil prices, it might mean that the interest rate differential becomes a bigger driver,” he said in an interview.

In an April 10 news conference, Macklem told reporters he’s watching currency moves as he’s weighing rate decisions. “If the Canadian dollar does move, that’s something that we’ll take into account in terms of our outlook.”

Most economists see Canada’s economy headed for a soft landing. That makes it harder for anyone to forecast how quickly rates will fall after easing begins — including Macklem and his officials.

“The bank probably doesn’t have a great deal of conviction around the precise path for this easing cycle, and there is no upside to guiding the market more than a meeting or two into the future,” Kelvin said.

Macklem is in Washington for the International Monetary Fund and World Bank meetings and will speak to reporters on Friday afternoon.